In 1811, a large comet streaked through the skies above the United States, an event that many Americans found fascinating—and others, terrifying. The comet's arrival seemed strange enough, but that same year, and again in 1812, the New Madrid fault line that runs from Missouri up through Tennessee shifted, causing two massive earthquakes. The quakes were so strong (registering more than 9.0 on the Richter Scale) that they tore the landscape apart and even forced the Mississippi River to run backwards for a brief period of time. Hundreds of aftershocks followed each earthquake, unsettling the population for weeks afterwards.

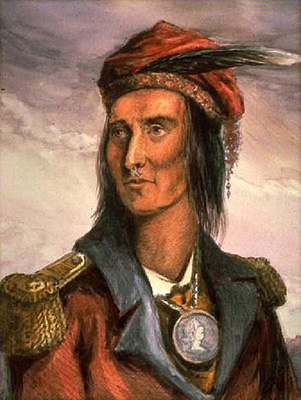

The Shawnee leader at the time was named Tecumseh. He and his brother, Tenskwatawa, who was also called the Prophet, took the two natural phenomena as signs that it was time for Native Americans to rise up and challenge the white man. Tough and charismatic, the two men riled and encouraged their followers, eventually leading them into the Creek, or Red Stick, Wars.

|

|

| The Shawnee Prophet, also known as Tenskwatawa. | The Shawnee Warrior, Tecumseh. |

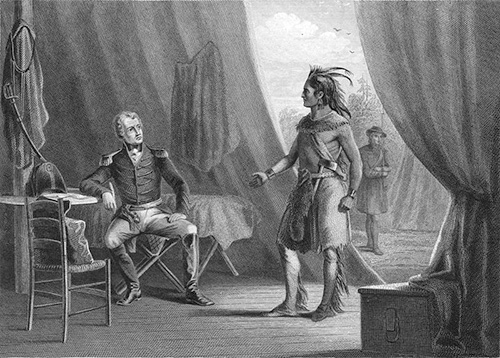

Andrew Jackson led U.S. troops in the fight against the Creek. The Creek War lasted less than two years, though the Creek gained some support from Great Britain, which also wished to limit the expansion of the United States. When the war was ended by the Treaty of Fort Jackson, General Jackson insisted that the Creek give up over 21 million acres of land from southern Georgia and central Alabama.

|

| A painting depicting Andrew Jackson and William Weatherford, known to the Creek as Lamochattee (Red Eagle), as he surrendered to Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. |

The Creek attempted to resist removal by passing a law that made it a capital crime to leave tribal lands. In 1825, the Creek were compelled to sign the Treaty of Indian Springs, surrendering their claim to all tribal lands in Georgia. Still, many Creeks tried to defy the treaty. They managed to negotiate another treaty with President John Quincy Adams in 1826. The Treaty of Washington was supposed to allow them to stay on their ancestral lands. However, the governor of Georgia was determined to seize control of Creek land for cultivation; in spite of the treaty, he sent his militia to remove the Creeks. In the end, President Adams was not able to back up the Treaty of Washington. He chose to back down rather than risk further conflict with Georgia.

Several thousand Creeks still remained in Alabama, but they were persecuted by local populations, and many were cheated out of their land by whites who wanted to expand their farms and plantations. During what historians loosely call "The Creek War of 1836," the U.S. government sent troops to force the Creeks from their lands in Alabama. More than 3,000 Creeks died on the long road to Indian Territory, or modern Oklahoma, where the survivors joined the Creeks already settled there.

Question

When fighting back proved less effective than they had hoped, what mechanism did the Creek use to delay or resist removal from their ancestral lands?