The early American colonies certainly had their differences. The Puritans had a rough start in the north but eventually developed a thriving system, and their population grew. Even though the establishment of Jamestown in Virginia was ultimately a failure, the colonists continued with the cultivation of tobacco. The colonies in the south were successful in the way of cash crop agriculture.

Watch the following video about the differences in the colonies and take notes.

![]() During the 16th and 17th centuries, many Europeans were moving to the Americas. They came for different reasons to the new colonies. The Puritans in the north were setting up a new religious government. The middle colonies were a mix of many different peoples and cultures. Many were settling in the south to establish plantations and make money on agriculture.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, many Europeans were moving to the Americas. They came for different reasons to the new colonies. The Puritans in the north were setting up a new religious government. The middle colonies were a mix of many different peoples and cultures. Many were settling in the south to establish plantations and make money on agriculture.

Pre-revolutionary America was a very diverse place indeed. The most diverse places were the middle colonies of Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware. More different ethnic groups lived in closer proximity than in any other place in Europe. The middle colonies had many Native American tribes and African slaves during the early years as well. Unlike New England with the Puritans, the middle colonies had a variety of religions. Quakers, Mennonites, Lutherans, Dutch Calvinists and Presbyterians made the presence of one faith impossible.

The largest cities in America were New York and Philadelphia. These cities had culture and gave rise to such notable thinkers as Benjamin Franklin, who earned his respect in America and Europe. The middle colonies were a hodgepodge of people and served as a cultural thinking spot. The middle colonies also had fertile soil. Land was easily acquired. The wheat and corn from these areas would feed the American colonies through the Revolutionary War. The middle colonies also maintained the middle ground between the north and the south. Elements from both towns and large estates could be found. These were the perfect nucleus for English America.

Virginia was the first successful southern colony. While Puritan enthusiasm was fueling New England's commercial development, and Penn's Quaker experiment was turning the middle colonies into America's bread basket, the South was turning to cash crops. Geography and motive made these colonies different from the others.

Directly to Virginia's north was Maryland. Maryland’s colonial economy would soon come to reflect that of Virginia as tobacco became the most important crop. To the south lay the Carolinas. In the Deep South was Georgia, the last of the original thirteen colonies. English American southerners would not enjoy the commonly good health of their New England counterparts. Outbreaks of malaria and yellow fever made life expectancies lower. Since the northern colonies attracted religious refugees, they tended to bring families in. Such family connections were less prevalent in the south.

Similarities & Differences Assignment

Similarities & Differences Assignment

Once you have viewed the presentation, write a 1-2 page paper on the differences and similarities between the American colonies in the north, middle and south. Include specific information about people, places, and things. Use the information below to help you. When you have completed the assignment, submit it to your teacher.

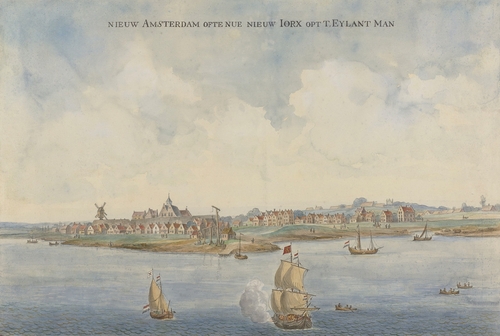

This Dutch painting by an anonymous artist shows New Amsterdam (New York City) around 1660.

England controlled two clusters of colonies in the early 1600s – Massachusetts and surrounding areas and Virginia. Through the early to mid-1600s, the English were in the middle of a civil war that saw the execution of King Charles I, the rise of a dictator named Oliver Cromwell, and the return of the king’s son, Charles II. While they were busy, other European nations, like the Dutch, tried to fill in other areas of the Atlantic Coast of North America.

In 1621, a group of Dutch merchants formed the Dutch West India Company to trade in the Americas. Their posts along the Hudson River grew into the colony of New Netherland. The main settlement of the colony was New Amsterdam, located on Manhattan Island. In 1626, the company bought Manhattan from the Manhates people for small quantities of beads and other goods. A good seaport, the city of New Amsterdam soon became a center of shipping to and from the Americas. To increase the number of permanent settlers in its colony, the Dutch West India Company sent over families from the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, and Finland. The company gave a large estate to anyone who brought at least 50 settlers to work the land. The wealthy landowners who acquired these riverfront estates were called patroons. The patroons ruled like kings. They had their own courts and laws. Settlers owed the patroon labor and a share of their crops.

Once stable again, the English wanted the valuable Dutch colony. In 1664, the English sent a fleet to attack New Amsterdam. At the time, Peter Stuyvesant was governor of the colony. His strict rule and heavy taxes turned many of the people in New Netherland against him. When the English ships sailed into New Amsterdam’s harbor, the governor was unprepared for a battle and surrendered the colony to the English forces. King Charles II gave the colony to his brother, the Duke of York, who renamed it New York. New York was a proprietary colony, a colony in which the owner, or proprietor, owned all the land and controlled the government. It differed from the New England Colonies, where voters elected the governor and an assembly. Most of New York’s settlers lived in the Hudson River valley. The Duke of York promised the diverse colonists freedom of religion. In 1654, 23 Brazilian Jews settled in New Amsterdam. They were the first Jews to settle in North America.

In 1664, New York had about 8,000 inhabitants. Most were Dutch, but Germans, Swedes, Native Americans, and Puritans from New England lived there as well. The population also included at least 300 enslaved Africans. New Amsterdam, which was later called New York City, was one of the fastest-growing locations in the colony. By 1683, the colony’s population had swelled to about 12,000 people. A governor and council appointed by the Duke of York directed the colony’s affairs. The colonists demanded a representative government like the governments of the other English colonies. The duke resisted the idea, but the people of New York would not give up. Finally, in 1691, the English government allowed New York to elect a legislature.

This stamp, printed for the U.S. bicentennial in 1976, shows Sir George Carteret (1771-1847) and an old map of New Jersey.

The Duke of York gave the southern part of his colony, between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers, to Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. The proprietors named their colony New Jersey after the island of Jersey in the English Channel, where Carteret was born. To attract settlers, the proprietors offered large tracts of land and generous terms. They also promised freedom of religion, trial by jury, and a representative assembly. The assembly would make local laws and set tax rates.

Like New York, New Jersey was a place of ethnic and religious diversity. Because New Jersey had no natural harbors, however, it did not develop a major port or city like New York. The proprietors of New Jersey did not make the profits they had expected. Berkeley sold his share, West Jersey, in 1674. Carteret’s share, East Jersey, was sold in 1682. By 1702 New Jersey had passed back into the hands of the king, becoming a royal colony. The colonists continued to make local laws.

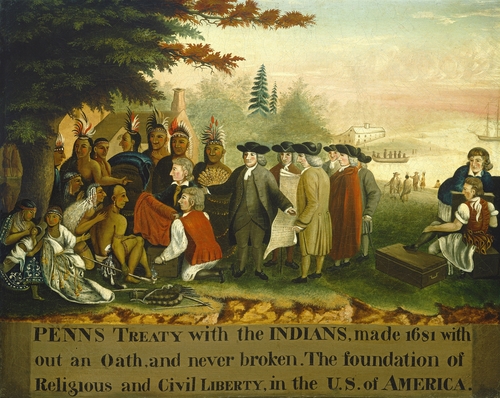

This oil painting by Edward Hicks, completed around 1840 to 1844, is titled "Penn's Treaty with the Indians." It shows William Penn entering a peace treaty with Tamanend, a chief of the Lenape Turtle Clan Delaware, in 1683.

In 1680, William Penn, a wealthy English gentleman, presented a plan to King Charles. Penn’s father had once lent the king a great deal of money. Penn had inherited the king’s promise to repay the loan. Instead of money, however, Penn asked for land in America. Pleased to get rid of his debt so easily, the king gave Penn a tract of land stretching inland from the Delaware River. The new colony, named Pennsylvania (“Penn’s Woods), was nearly as large as England.

William Penn belonged to a Protestant group of dissenters called the Society of Friends, or Quakers. The Quakers believed that every individual had an “inner light” that could guide him or her to salvation. Each person could experience religious truth directly, which meant that church services and officials were unnecessary. Everyone was equal in God’s sight. Though firm in their beliefs, the Quakers were tolerant of the views of others. Many in England found their ideas a threat to established traditions. Quakers would not bow or take off their hats to lords and ladies because of their belief that everyone was equal. In addition, they were pacifists, people who refuse to use force or to fight in wars. Quakers were fined, jailed, and even executed for their beliefs.

Penn saw Pennsylvania as a “holy experiment,” a chance to put the Quaker ideals of toleration and equality into practice. In 1682, he sailed to America to supervise the building of Philadelphia, the “city of brotherly love.” Penn designed the city himself, making him America’s first town planner. Penn also wrote Pennsylvania’s first constitution. He believed that the land belonged to the Native Americans and that settlers should pay for it. In 1682, he negotiated the first of several treaties with local Native Americans.

To encourage European settlers to come to Pennsylvania, Penn advertised the colony throughout Europe with pamphlets in several languages. By 1683, more than 3,000 English, Welsh, Irish, Dutch, and German settlers had arrived. In 1701, in the Charter of Liberties, Penn granted the colonists the right to elect representatives to a legislative assembly. The southernmost part of Pennsylvania was called the Three Lower Counties. Settled by Swedes in 1638, the area had been taken over by the Dutch and the English before becoming part of Pennsylvania. The Charter of Privileges allowed the lower counties to form their own legislature, which they did in 1704. Thereafter the counties functioned as a separate colony known as Delaware, supervised by Pennsylvania’s governor.

Rapids in the Potomac River at Great Falls, as seen from Olmsted Island at Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park in Maryland

Maryland was the dream of Sir George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, a Catholic Recusant. Calvert wanted to establish a safe place for his fellow Catholics, who were being persecuted in England. He also hoped that a colony would bring him a fortune. In 1632, King Charles I (who was sympathetic to Catholics) gave him a proprietary colony north of Virginia. Calvert died before receiving the grant, but his son Cecilius Calvert inherited the colony. It was named Maryland either after the English queen, Henrietta Maria, or after the Virgin Mary.

The younger Calvert never lived in Maryland but sent two of his brothers to run the colony. They reached America in 1634 with two ships and more than 200 settlers. Entering Chesapeake Bay, they sailed up the Potomac River through fertile countryside. A priest in the party described the Potomac as “the sweetest and greatest river I have ever seen.” The colonists chose a site for their settlement, which they called St. Mary’s.

The Maryland colonists turned first to tobacco farming, but to keep things diverse, also required corn to be planted. In addition to corn, most Maryland farmers produced wheat, fruit, vegetables, and livestock to feed their families and their workers. Baltimore, founded in 1729, was Maryland’s port. Before long, it became the colony’s largest settlement. Lord Baltimore gave large estates to his relatives and other English aristocrats. By doing so, he created a wealthy and powerful class of landowners in Maryland. The colony needed people to work in the plantation fields. To bring settlers to the colony, Lord Baltimore promised land—100 acres to each male settler, another 100 for his wife, 100 for each servant, and 50 for each of his children. As the number of plantations increased and additional workers were needed, the colony imported indentured servants and enslaved Africans.

The Calverts and the Penns argued over the boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania. In the 1760s, they hired two British astronomers, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, to map the line dividing the colonies. It took the two scientists many years to lay out the boundary stones. Each stone had the crest of the Penn family on one side and the crest of the Calverts on the other.

Another conflict was even harder to resolve. The Calverts had welcomed Protestants as well as Catholics in Maryland. Protestant settlers outnumbered Catholics from the start. To protect the Catholics from any attempt to make Maryland a Protestant colony, Baltimore passed a law called the Act of Toleration in 1649. The act granted Protestants and Catholics the right to worship freely, but tensions continued between Protestants and Catholics. In 1692, with the support of the English government, the Protestant-controlled assembly made the Anglican Church the official church in Maryland and imposed the same restrictions on Catholics that existed in England.

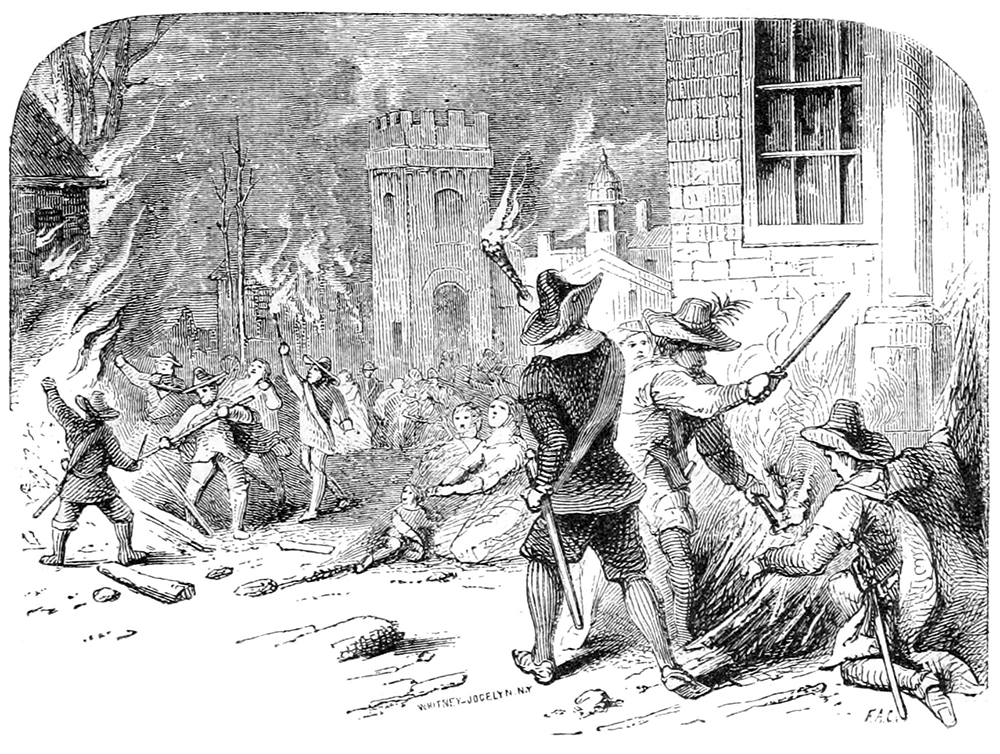

This drawing shows the burning of Jamestown during Bacon's Rebellion in 1676. The image comes from Illustrated School History of the United States and the Adjacent Parts of America: from the Earliest Discoveries to the Present Time (1857).

While other colonies were being founded, Virginia continued to grow. Wealthy tobacco planters held the best land near the coast, so new settlers pushed inland. As the settlers moved west, they found the lands inhabited by Native Americans. In the 1640s, to avoid conflicts, Virginia’s governor William Berkeley worked out an arrangement with the Native Americans. In exchange for a large piece of land, he agreed to keep settlers from pushing farther into their lands.

Nathaniel Bacon, a wealthy young planter, was a leader in the western part of Virginia. He and other westerners opposed the colonial government because it was dominated by easterners. Many of the westerners resented Berkeley’s pledge to stay out of Native American territory. Some of them settled in the forbidden lands and then blamed the government in Jamestown for not protecting them from Native American raids.

In 1676, Bacon led the angry westerners in attacks on Native American villages. Bacon’s army marched to Jamestown, set fire to the capital, and drove Berkeley into exile. Only Bacon’s sudden illness and death kept him from taking charge of Virginia. England then recalled Berkeley and sent troops to restore order. Bacon’s Rebellion had shown that the settlers were not willing to be restricted to the coast. The colonial government created a militia force to control the Native Americans and opened up more land to settlement.

A portrait of John Locke from 1697

In 1663, King Charles II created a large proprietary colony south of Virginia. The colony was called Carolina, which means “Charles’s land” in Latin. The king gave the colony to a group of eight prominent members of his court who had helped him regain his throne. The proprietors carved out large estates for themselves and hoped to make money by selling and renting land. The proprietors provided money to bring colonists over from England. Settlers began arriving in Carolina in 1670. By 1680, they had founded a city, which they called Charles Town after the king. The name later became Charleston.

John Locke, an English political philosopher, wrote a constitution for the Carolina colony. This constitution, or plan of government, covered such subjects as land distribution and social ranking. Locke was concerned with principles and rights. Carolina, however, did not develop according to plan. The people of northern and southern Carolina soon went their separate ways, creating two colonies.

The northern part of Carolina was settled mostly by farmers from Virginia’s backcountry. They grew tobacco and sold forest products such as timber and tar. Because the northern Carolina coast did not have a good harbor, the farmers relied on Virginia’s ports and merchants to conduct their trade. The southern part of the Carolinas was more prosperous, thanks to fertile farmland and a good harbor at Charles Town. Settlements spread, and the trade in deerskin, lumber, and beef flourished. In the 1680s, planters discovered that rice grew well in the wet coastal lowlands., and it soon became the colony’s leading crop. In the 1740s, a young Englishwoman named Eliza Lucas developed another important Carolina crop, indigo. Indigo, a blue flowering plant, was used to dye textiles. After experimenting with seeds from the West Indies, Lucas succeeded in growing and processing indigo, the “blue gold” of Carolina.

Most of the settlers in southern Carolina came from another English colony – the island of Barbados in the West Indies. In Barbados, the colonists used enslaved Africans to produce sugar. The colonists brought these workers with them. Many enslaved Africans who arrived in the Carolinas worked in the rice fields. Some of them knew a great deal about rice cultivation because they had come from the rice-growing areas of West Africa. Growing rice required much labor, so the demand for slaves increased. By 1708, more than half the people living in southern Carolina were enslaved Africans. By the early 1700s, Carolina’s settlers were angry at the proprietors. They wanted a greater role in the colony’s government. In 1719, the settlers in southern Carolina seized control from its proprietors. In 1729, Carolina became two royal colonies, North and South Carolina.

This map shows the British Empire in America and the nearby French and Spanish settlements in 1733.

Georgia, the last of the British colonies in America to be established, was founded in 1733. A group led by General James Oglethorpe received a charter to create a colony where English debtors and poor people could make a fresh start. In Great Britain, debtors, those who are unable to repay their debts, were generally thrown into prison. The British government had another reason for creating Georgia. This colony could protect the other British colonies from Spanish attack. Great Britain and Spain had been at war in the early 1700s, and new conflicts over territory in North America were always breaking out. Located between Spanish Florida and South Carolina, Georgia could serve as a military barrier.

Oglethorpe built a town called Savannah, as well as forts to defend against the Spanish. Oglethorpe wanted the people of Georgia to be hardworking, independent, and Protestant. He kept the size of farms small and banned slavery, Catholics, and rum. Although Georgia had been planned as a debtors’ colony, it received few debtors. Hundreds of poor people came from Great Britain instead. Religious refugees from Germany and Switzerland and a small group of Jews also settled there. Georgia soon had a higher percentage of non-British settlers than any other British colony in the Americas.

Many settlers complained about limits on the size of landholdings and the law banning slave labor. They also objected to the many rules Oglethorpe made regulating their lives. Oglethorpe grew frustrated by the colonists’ demands and the colony’s slow growth. He agreed to let people have larger landholdings and lifted the bans against slavery and rum. In 1751, he gave up altogether and turned the colony back over to the king. By that time, British settlers had been in what is now the eastern United States for almost a century and a half. They had lined the Atlantic coast with colonies.

You will be graded using the following rubric.

| Expert (3 points) | Strong (2 points) | Beginning (1 point) | |

| Focus & Details | There is one clear, well-focused topic. Main ideas are clear and are well supported by detailed and accurate information. | There is one topic. Main ideas are somewhat clear. | The topic and main ideas are not clear. |

| Organization | The introduction is inviting, states the main topic, and provides an overview of the paper. Information is relevant and presented in a logical order. The conclusion is strong. | The introduction states the main topic. A conclusion is included. | There is no clear introduction, structure, or conclusion. |

| Voice | The author’s purpose for writing is very clear, and there is strong evidence of attention to audience. The author’s extensive knowledge of the topic is evident. | The author’s purpose for writing is somewhat clear, and there is evidence of attention to audience. The author’s knowledge of the topic is limited. | The author’s purpose for writing is unclear. |

| Word Choice | The author uses vivid words and phrases. The choice and placement of words seems accurate, natural, and not forced. | The author uses words that communicate clearly, but the writing lacks variety. | The writer uses a limited vocabulary. Jargon or clichés may be present and detract from the meaning. |

| Syntax | All sentences are well constructed and have varied structure and length. The author makes no errors in grammar, mechanics, and/or spelling. | Most sentences are well constructed, but they have a similar structure and/or length. The author makes several errors in grammar, mechanics, and/or spelling that interfere with understanding. | Sentences sound awkward, are distractingly repetitive, or are difficult to understand. The author makes numerous errors in grammar, mechanics, and/or spelling that interfere with understanding. |