Most readers, when presented with a series of explicit details, automatically begin to interpret those details. They use what they know or can see to arrive at other ideas about the topic. In other words, they make inferences—“educated” guesses based on the evidence.

Suppose a friend of yours has described her brother to you, at various times, using these sentences:

- Mark always wears basketball shorts and tennis shoes.

- When he comes home from practice, Mark is covered in sweat.

- Mark is the tallest person in his class.

- There are over twenty basketball trophies on display in Mark's bedroom.

- Even though he doesn't graduate for two more years, Mark is hoping for a basketball scholarship.

You would probably interpret these details to mean that Mark is a basketball player, and that he is very good at the sport. You would discover an implicit detail about Mark, using the evidence provided by explicit details.

Implicit details can lead speakers or writers to share explicit details as well. If you were to tell a friend that Mark is very good at basketball, he or she might ask why you think so. Then you could list the same set of explicit details Mark’s sister said to you. Those details would make your description of Mark more explicit and therefore easier to believe.

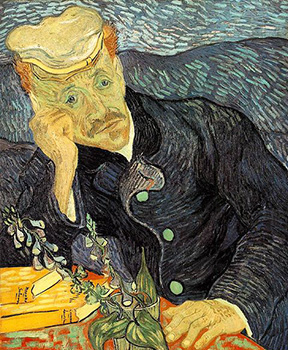

Take a look at Vincent van Gogh's painting Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890). This is one of van Gogh’s most famous paintings because viewers are always fascinated by the emotion on Dr. Gachet’s face. Dr. Gachet’s emotion is an implicit detail, meaning viewers infer Dr. Gachet's emotion by interpreting the painting's explicit details.

Question

How do most people interpret Dr. Gachet's mood?

Question

What explicit details lead most viewers to interpret Dr. Gachet's mood in this way?