Beginning in 1811, a group of young, ambitious American men began to favor expansion of the United States. These men, called war hawks, wanted to take land in Canada and other lands further in the south and Midwest from the British.

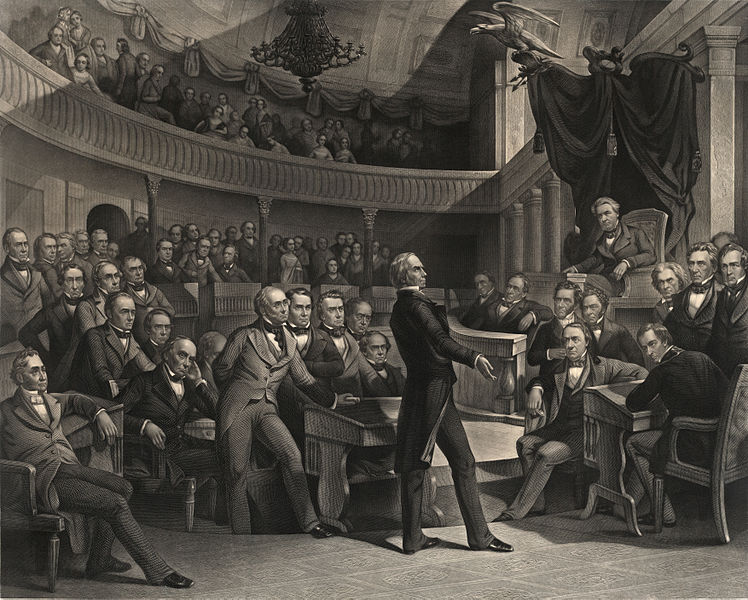

Notable hawks included the Speaker of the House Henry Clay. Clay called for war against Britain and targeted expansion into Canada. The southern war hawks, led by John C. Calhoun, had their sights on Texas and Florida, both Spanish possessions.

The war hawks not only favored the expansion of the United States but also wanted the British out of North America. The list of grievances against the British was growing, and the War of 1812 between the Americans and British loomed on the horizon.

Read and take notes on the War of 1812.

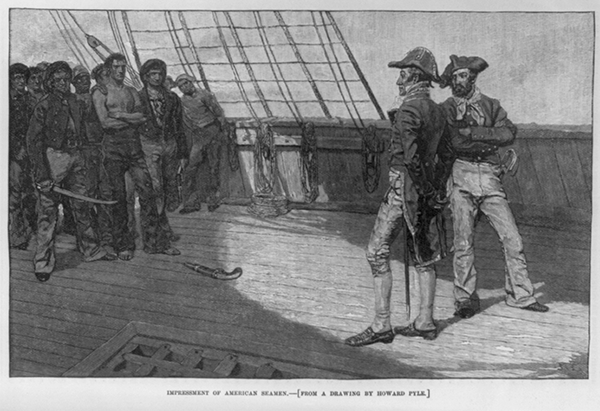

Artwork depicting the impressment of American seamen by the British Navy

Madison’s concerns with growing foreign tension went back to the first term of Jefferson. Across the sea, Great Britain and France were already involved in a war that threatened to interfere with American trade. The thriving foreign trade of the United States depended on being able to sail the seas freely. The nation had resolved the threat from the Barbary pirates. Now it was challenged at sea by the two most powerful nations in Europe.

When Britain and France went to war in 1803, America enjoyed a prosperous commerce with both countries. As long as the United States remained neutral, shippers could continue doing business. A nation not involved in a conflict had neutral rights, or the right to sail the seas and not take sides. For two years, American shipping continued to prosper. By 1805, however, the warring nations had lost patience with American “neutrality.”

Britain blockaded the French coast and threatened to search all ships trading with France. France later announced that it would search and seize ships caught trading with Britain. The British needed sailors for their naval war. Conditions in the British Royal Navy were terrible. British sailors were poorly paid, poorly fed, and badly treated. Many of them deserted. Desperately in need of sailors, the British often used force to get them. British naval patrols claimed the right to stop American ships at sea and search for any sailors on board suspected of being deserters from the British navy. This practice of forcing people to serve in the navy was called impressment. While some of those taken were deserters from the British navy, the British also impressed thousands of native-born and naturalized American citizens.

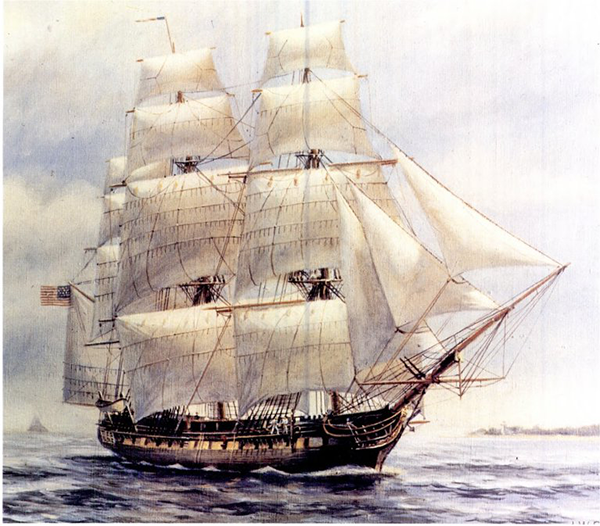

A drawing of the USS Chesapeake

Quite often, the British would lie in wait for American ships outside an American harbor. This happened in June 1807 off the coast of Virginia. A British warship, the Leopard, intercepted the American vessel Chesapeake and demanded to search the ship for British deserters. When the Chesapeake’s captain refused, the British opened fire, killing 3, wounding 18, and crippling the American ship. As news of the attack spread, Americans reacted with an anti-British fury not seen since the Revolutionary War. Secretary of State James Madison called the attack an outrage. Many demanded war against Britain. Although Jefferson did not intend to let Great Britain’s actions go unanswered, he sought a course of action other than war.

Britain’s practice of impressment and its violation of America’s neutral rights had led Jefferson to ban some trade with Britain. The attack on the Chesapeake triggered even stronger measures. In December 1807, the Republican Congress passed the Embargo Act. An embargo prohibits trade with another country. Although Great Britain was the target of this act, the embargo banned imports from and exports to all foreign countries. Jefferson wanted to prevent Americans from using other countries as go-betweens in the forbidden trade.

With the embargo, Jefferson and Madison hoped to hurt Britain but avoid war. They believed the British depended on American agricultural products. As it turned out, the embargo of 1807 was a disaster. The measure destroyed all American commerce with other nations. Worse, it proved ineffective against Britain. The British simply traded with Latin America for its agricultural goods. The embargo clearly had not worked. On March 1, 1809, Congress repealed it. In its place Congress enacted the much weaker Nonintercourse Act. The new act prohibited trade only with Britain and France and their colonial possessions. It was no more popular or successful than the Embargo Act.

A portrait of Henry Clay

As Madison took office, Britain continued to claim the right to halt American ships, and cries for war with Britain grew louder. In 1810, Congress passed a law permitting direct trade with either France or Britain, depending on which country first lifted its trade restrictions against America. French Emperor Napoleon seized the opportunity and promised to end France’s trade restrictions. Unfortunately for Madison, Napoleon had tricked the American administration. The French continued to seize American ships, selling them and pocketing the proceeds. Americans were deeply divided. To some, it seemed as if the nation was on the verge of war, but it was hard to decide if the enemy should be Britain or France. Madison knew that France had tricked him, but he continued to see Britain as the bigger threat to the United States.

In the nation’s capital, Madison faced demands for a more aggressive policy toward the British. The most insistent voices came from a group of young Republicans elected to Congress in 1810. Known as the War Hawks, they came from the South and the West. The War Hawks pressured the president to declare war against Britain. While the War Hawks wanted to avenge British actions against Americans, they were also eager to expand the nation’s power. Their nationalism, or loyalty to their country, appealed to a renewed sense of American patriotism.

The leading War Hawks were Henry Clay from Kentucky and John Calhoun from South Carolina, both in their 30s. Hunger for land heightened war fever. Westerners wanted to move north into the fertile forests of southern Canada. A war with Britain might make Canadian land available. Southerners wanted Spanish Florida. The War Hawks urged major military spending. Through their efforts, Congress quadrupled the army’s size. The Federalists in the Northeast, however, remained strongly opposed to the war.

Soldiers march into battle during a War of 1812 reenactment at Stoney Creek, Ontario, Canada, on June 6, 2011.

By the spring of 1812, Madison concluded that war with Britain was inevitable. In a message to Congress on June 1, he cited “the spectacle of injuries and indignities which have been heaped on our country” and asked for a declaration of war. In the meantime, the British had decided to end their policy of search and seizure of American ships. Unfortunately, because of the amount of time it took for news to travel across the Atlantic, this change in policy was not known in Washington. Word of the breakthrough arrived too late. Once set in motion, the war machine could not be stopped.

Despite their swaggering songs, the War Hawks did not achieve the quick victory they boldly predicted. The Americans committed a series of blunders that showed how unprepared they were for war. The regular army now consisted of fewer than 7,000 troops. The states had between 50,000 and 100,000 militia, but the units were poorly trained, and many states opposed “Mr. Madison’s war.” The military commanders, veterans of the American Revolution, were too old for warfare, and the government in Washington provided no leadership. The Americans also underestimated the strength of the British and their Native American allies.

The war started in July 1812, when General William Hull led the American army from Detroit into Canada. Hull was met by Tecumseh and his warriors. Fearing a massacre by the Native Americans, Hull surrendered Detroit to a small British force in August. Another attempt by General William Henry Harrison was unsuccessful as well. Harrison decided that the Americans could make no headway in Canada as long as the British controlled Lake Erie.

Artwork depicting the Battle of the Thames and the death of Tecumseh

Oliver Hazard Perry, commander of the Lake Erie naval forces, had his orders. He was to assemble a fleet and seize the lake from the British. From his headquarters in Put-in-Bay, Ohio, Perry could watch the movements of the enemy ships. The showdown came on September 10, 1813, when the British ships sailed out to face the Americans. In the bloody battle that followed, Perry and his ships defeated the British naval force. After the battle, Perry sent General William Henry Harrison the message, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.”

With Lake Erie in American hands, the British and their Native American allies tried to pull back from the Detroit area. Harrison and his troops cut them off. In the fierce Battle of the Thames on October 5, the great leader Tecumseh was killed. The Americans also attacked the town of York (present-day Toronto, Canada), burning the parliament buildings. Canada remained unconquered, but by the end of 1813 the Americans had won some victories on land and at sea.

To lower the national debt, the Republicans had reduced the size of the navy. However, the navy still boasted three of the fastest frigates, or warships, afloat. Americans exulted when the Constitution, one of these frigates, destroyed two British vessels—the Guerrière in August 1812 and the Java four months later. After seeing a shot bounce off the Constitution’s hull during battle, a sailor nicknamed the ship “Old Ironsides.” American privateers, armed private ships, also staged spectacular attacks on British ships and captured numerous vessels. These victories were more important for morale than for their strategic value.

Francis Scott Key awakes on September 14, 1814, to see the American flag still waving over Fort McHenry.

British fortunes improved in the spring of 1814. They had been fighting a war with Napoleon and had won. Now, they could send more forces to America. August 24, 1814 was a low point for the Americans, the British sailed into Chesapeake Bay. Their destination was Washington, D.C. On the outskirts of the city, the British troops quickly overpowered the American militia and then marched into the city. “They proceeded, without a moment’s delay, to burn and destroy everything in the most distant degree connected with government,” reported a British officer. The Capitol and the president’s mansion were among the buildings burned. Watching from outside the city, Madison and his cabinet saw the night sky turn orange. Fortunately, a strong thunderstorm, including a violent tornado, put out the fires before they could do more damage.

Much to everyone’s surprise, the British did not try to hold Washington. They left the city and sailed north to Baltimore. Baltimore was ready and waiting with barricaded roads, a blocked harbor, and some 13,000 militiamen. The British attacked in mid-September. They were kept from entering the town by a determined defense and ferocious bombardment from Fort McHenry in the harbor. During the night of September 13–14, a young attorney named Francis Scott Key watched as the bombs burst over Fort McHenry. Finally, “by the dawn’s early light,” Key was able to see that the American flag still flew over the fort. Deeply moved by patriotic feeling, Key wrote a poem called “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

This painting shows General Andrew Jackson commanding U.S. troops in the Battle of New Orleans. The British troops marched into American fire from a fortified line on January 8, 1815.

Meanwhile, in the north, General Sir George Prevost led more than 10,000 British troops into New York State from Canada. The first British goal was to capture Plattsburgh, a key city on the shore of Lake Champlain. The invasion was stopped when an American naval force on Lake Champlain defeated the British fleet on the lake in September 1814. Knowing the American ships could use their control of the lake to bombard them and land troops behind them, the British retreated to Canada.

After the Battle of Lake Champlain, the British decided the war in North America was too costly and unnecessary. Napoleon had been defeated in Europe. To keep fighting the United States would gain little and was not worth the effort. American and British representatives signed a peace agreement in December 1814 in Ghent, Belgium. The Treaty of Ghent did not change any existing borders. Nothing was mentioned about the impressment of sailors, but, with Napoleon’s defeat, neutral rights had become a dead issue.

Before word of the treaty had reached the United States, one final and ferocious battle occurred at New Orleans. In December 1814, British army troops moved toward New Orleans. Awaiting them behind earthen fortifications was an American army led by Andrew Jackson. On January 8, 1815, the British troops advanced. The redcoats were no match for Jackson’s soldiers, who shot from behind bales of cotton. In a short but gruesome battle, hundreds of British soldiers were killed. At the Battle of New Orleans, Americans achieved a decisive victory. Andrew Jackson became a hero, and his fame helped him win the presidency in 1828.

New England Federalists had opposed “Mr. Madison’s war” from the start. In December 1814, unhappy New England Federalists gathered in Connecticut at the Hartford Convention. A few favored secession. Most wanted to remain within the Union, however. To protect their interests, they drew up a list of proposed amendments to the Constitution. After the convention broke up, word came of Jackson’s spectacular victory at New Orleans, followed by news of the peace treaty. In this moment of triumph, the Federalist grievances seemed unpatriotic. The party lost respect in the eyes of the public. Most Americans felt proud and self-confident at the end of the War of 1812. The young nation had gained new respect from other nations in the world. Americans felt a new sense of patriotism and a strong national identity. Although the Federalist Party weakened, its philosophy of strong national government was carried on by the War Hawks who were part of the Republican Party. They favored trade, western expansion, the energetic development of the economy, and a strong army and navy.