In 1870, about half of the nation's children received no formal education whatsoever. Kids were often too busy working on farms, in factories, or in mines to go to school. During the Gilded Age, however, many people were calling for a better--and mandatory, or required--education system.

Many scholars and politicians felt that a well-educated populace was a cornerstone of democracy. Moreover, educated workers would be smarter workers and potentially more productive. The late 1800s saw the beginning of compulsory education, a boom in school building, and growth in colleges, specifically for women and African Americans. The downside to this was that Jim Crow laws in the South often meant separate schools for blacks and whites.

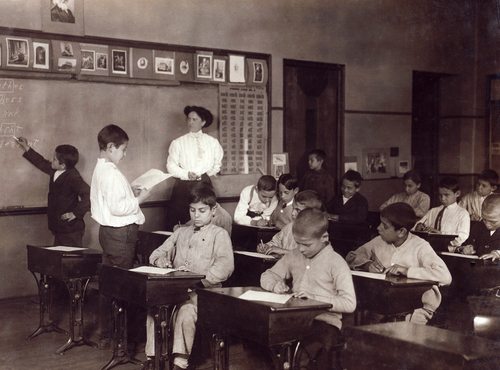

The Steamer Class in the Washington School in Boston, Massachusetts, in October 1909; photo by Lewis Wickes Hine

Most Americans in 1865 had attended school for an average of only four years. Government and business leaders and reformers believed that for the nation to progress, the people needed more schooling. Toward the end of the 1800s, education became more widely available to Americans. By 1914, most states required children to have at least some schooling. More than 80 percent of all children between the ages of 5 and 17 were enrolled in elementary and secondary schools.

The expansion of public education was particularly notable in high schools. The number of public high schools increased from 100 in 1860 to 6,000 in 1900, and increased to 12,000 in 1914. Despite this huge increase, however, many teenagers did not attend high school. Boys often went to work to help their families instead of attending school. Most high school students were girls. The benefits of a public school education were not shared equally by everyone. In the South, many African Americans received little or no education. In many parts of the country, African American children had no choice but to attend segregated elementary and secondary schools.

Around 1900, a new philosophy of education emerged in the United States. Supporters of this “progressive education” wanted to shape students’ characters and teach them good citizenship as well as facts. They also believed children should learn by “hands-on” activities. These ideas had the greatest effect in elementary schools. John Dewey, the leading spokesperson for progressive education, criticized schools for overemphasizing memorization of information. Instead, Dewey argued, schools should relate learning to the interests, problems, and concerns of students.

Billings Hall at Wellesley College in Wellesley, Massachusetts

Colleges and universities also changed and expanded. An 1862 law called the Morrill Act gave the states large amounts of federal land that could be sold to raise money for education. The states used these funds to start dozens of schools called land-grant colleges. Wealthy individuals also established and supported colleges and universities. Some schools were named for the donors, for example, Cornell University for Ezra Cornell and Stanford University for Leland Stanford.

In 1865, only a handful of American colleges admitted women. The new land-grant schools admitted women students, as did new women’s colleges like Vassar, Smith, Wellesley, and Bryn Mawr that were founded in the late 1800s. By 1890, women could attend a wide range of schools, and by 1910 almost 40 percent of American college students were women.

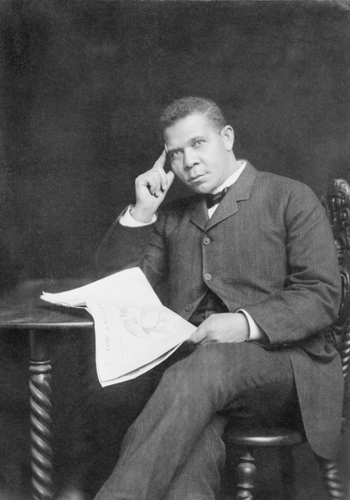

Booker T. Washington

Some new colleges, such as Hampton Institute in Virginia, provided higher education for African Americans and Native Americans. Howard University in Washington, D.C., founded shortly after the Civil War, had a largely African American student body. By the early 1870s, Howard offered degrees in theology, medicine, law, and agriculture.

One Hampton Institute student, Booker T. Washington, became an educator. In 1881, Washington founded the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to train teachers and to provide practical education for African Americans. As a result of his work as an educator and public speaker, Washington became influential in business and politics. In 1896, scientist George Washington Carver joined the Tuskegee faculty. His research transformed agricultural development in the South. From the peanut, which was formerly of little use, Carver developed hundreds of products, including plastics, synthetic rubber, shaving cream, and paper.

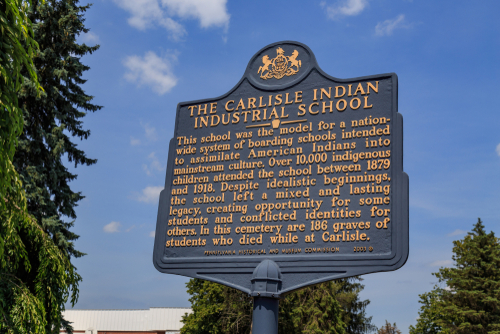

A historic marker at the grave site of Native Americans who attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania

Reservation schools and boarding schools also opened to train Native Americans for jobs. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania was founded in 1879, and similar schools opened in the West. Although these schools provided Native Americans with training for jobs in industry, they also isolated Native Americans from their tribal traditions. Sometimes, boarding schools were located hundreds of miles away from a student’s family.

| By 1870, how many of America's children were not receiving a formal education? | around half |

| What laws in the South ensured that education was completely segregated by race? | Jim Crow laws |

| By 1910, what percentage of college students were female? | about 40% |