Where Did Your Ancestors Come From?

America is a nation of immigrants, but where did they come from? For most Americans, the answer to this question lies in a country other than the U.S. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, millions upon millions of people moved to the United States. As a growing nation with needs for settlers and industrial workers, the United States welcomed many of them. However, not all were welcome.

A push-cart market on Manhattan's Lower East Side around 1915; Jewish immigrants operated these mobile businesses as their first enterprises.

Before 1865, most immigrants to the United States, except for the enslaved, came from northern and western Europe. The greater part of these “old” immigrants were Protestant, spoke English, and blended easily into American society. After the Civil War, even greater numbers of immigrants made the journey to the United States. The tide of newcomers reached a peak in 1907 when nearly 1.3 million people came to America.

In the 1880s the pattern of immigration started to change. Large groups of “new” immigrants arrived from eastern and southern Europe. Greeks, Russians, Hungarians, Italians, Turks, and Poles were among the newcomers. At the same time, the number of “old” immigrants started to decrease. By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, only about 20 percent of the immigrants came from northern and western Europe, while 80 percent came from southern and eastern Europe.

Many of the newcomers from eastern and southern Europe were Catholics or Jews. Few spoke English. Because of this, they did not blend into American society as easily as the “old” immigrants had. Many felt like outsiders, and they clustered together in urban neighborhoods made up of people of the same nationality. After 1900, immigration from Mexico also increased. In addition, many people came to the United States from China and Japan. They, too, brought unfamiliar languages and religious beliefs and had difficulty blending into American society.

A crowd of European immigrants and their luggage on the Imperator, then the world's largest ocean liner, arriving in New York Harbor on June 19, 1913, with over 4,000 passengers

Why did so many people leave their homelands for the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s? They were “pushed” away by difficult conditions at home and “pulled” to the United States by new opportunities. Many people emigrated, or left their homelands, because of economic troubles. In Italy and Hungary, overcrowding and poverty made jobs scarce. Farmers in Croatia and Serbia could not own enough land to support their families. Sweden suffered major crop failures. New machines such as looms put many craft workers out of work.

Persecution also drove people from their homelands. In some countries the government passed laws or followed policies against certain ethnic groups, minorities that spoke different languages or followed different customs from those of most people in a country. Members of these ethnic groups often emigrated to escape discrimination or unfair laws. Many Jews fled persecution in Russia in the 1880s and came to the United States.

Immigrants saw the United States as a land of jobs, plentiful and affordable land, and opportunities for a better life. Although some immigrants returned to their homelands after a few years, most came to America to stay. Immigrants often had a difficult journey to America. Many had to first travel to a seaport to board a ship. Often, they traveled for hundreds of miles on foot or on horseback and through foreign countries to get to the port cities. Then came the long ocean voyage to America—12 days across the Atlantic or several weeks across the Pacific. Immigrants usually could afford only the cheapest tickets, and they traveled in steerage—cramped, noisy quarters on the lower decks.

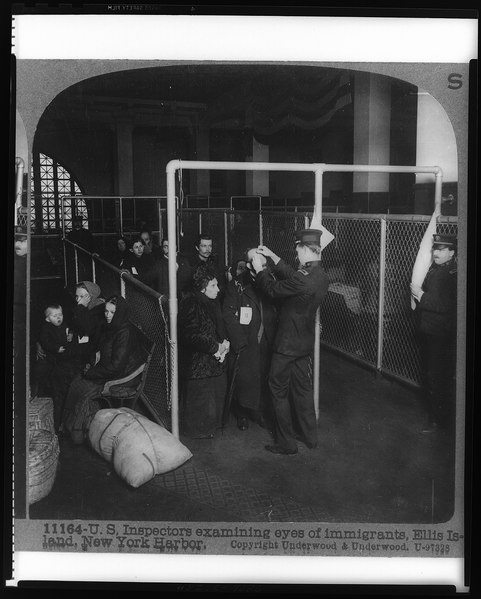

U.S. inspectors examine the eyes of immigrants on Ellis Island in 1913.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress / Public domain

Most European immigrants landed at New York City. After 1886, the magnificent sight of the Statue of Liberty greeted the immigrants as they sailed into New York Harbor. The statue, a gift from France, seemed to promise hope for a better life in the new country. On the base of the statue, the stirring words of Emma Lazarus, an American poet, welcomed immigrants from Europe: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

However, before the new arrivals could actually pass through the “golden door” to America, they had to register at government reception centers. In the East, immigrants were processed at Castle Garden, a former fort on Manhattan Island, and after 1892 at Ellis Island in New York Harbor. Most Asian immigrants arrived in America on the West Coast and went through the processing center on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay.

Examiners at the centers recorded the immigrants’ names, sometimes shortening or simplifying a name they found too difficult to write. The examiners asked the immigrants where they came from, their occupation, and whether they had relatives in the United States. The examiners also gave health examinations. Immigrants with contagious illnesses could be refused permission to enter the United States.

Italian men await admission processing at Ellis Island in 1910; they were among the 2,000 Italian immigrants who arrived on the Princess Irene.

A view from Rivington Street in New York City's Lower East Side Jewish neighborhood in 1909

After passing through the reception centers, most immigrants entered the United States. Some had relatives or friends to stay with and to help them find jobs. Others knew no one and would have to strike out on their own. An immigrant’s greatest challenge was finding work. Sometimes organizations in his or her homeland recruited workers for jobs in the United States. The organization supplied American employers with unskilled workers who worked unloading cargo or digging ditches. Some of America’s fastest-growing industries hired immigrant workers. In the steel mills of Pittsburgh, for example, most of the common laborers in the early 1900s were immigrant men. They might work 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Many immigrants, including women and children, worked in sweatshops in the garment industry. These were dark, crowded workshops where workers made clothing. The work was repetitious and hazardous, the pay low, and the hours long.

In their new homes, immigrants tried to preserve some aspects of their own cultures. At the same time, most wanted to assimilate, or become part of the American culture. These two desires sometimes came into conflict. Language highlighted the differences between generations. Many immigrant parents continued to speak their native languages. Their children spoke English at school and with friends, but they also spoke their native language at home. On the other hand, the grandchildren of many immigrants spoke only English. The role of immigrant women also changed in the United States, where women generally had more freedom than women in European and Asian countries. New lifestyles conflicted with traditional ways and sometimes caused family friction.

Most of the new immigrants were from rural areas. Because they lacked the money to buy farmland in America, however, they often settled in industrial cities. With little or no education, they usually worked as unskilled laborers. Relatives who had immigrated earlier helped new arrivals get settled, and people of the same ethnic group naturally tended to form communities. As a result, neighborhoods of Jewish, Italian, Polish, Chinese, and other groups quickly developed in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and other large cities.

The immigrants sought to re-create some of the life they had left behind. The communities they established revolved around a few traditional institutions. Most important were churches and synagogues where worship was conducted, and holidays were celebrated as they had been in their homelands. Priests and rabbis often acted as community leaders. The immigrants published newspapers in their native languages, opened stores and theaters, and organized social clubs. Ethnic communities and institutions helped the immigrants preserve their cultural heritage.

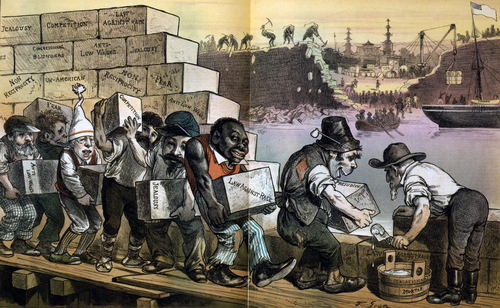

An 1882 chromolithograph represents the Chinese Exclusion Act by showing laborers building a wall against the Chinese.

Assimilation was also slowed by the attitudes of many native-born Americans. Although employers were happy to hire immigrant workers at low wages, some American-born workers resented the immigrants. These Americans feared that the immigrants would take away their jobs or drive down everyone’s wages by accepting lower pay. Ethnic, religious, and racial differences contributed to tensions between Americans and the new immigrants. Some Americans argued that the new immigrants, with their foreign languages, unfamiliar religions, and distinctive customs, did not fit into American society. People found it easy to blame immigrants for increasing crime, unemployment, and other problems. The nativist movement, for example, had opposed immigration since the 1830s. Nativism gained strength in the late 1800s. Calls for restrictions on immigration mounted.

Lawmakers responded quickly to the tide of anti-immigrant feeling. In 1882, Congress passed the first law to limit immigration, the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law prohibited Chinese workers from entering the United States for 10 years. Congress extended the law in 1892 and again in 1902. In 1907, the federal government and Japan came to a “gentleman’s agreement.” The Japanese agreed to limit the number of immigrants to the United States, while the Americans pledged fair treatment for Japanese Americans already in the United States. Other legislation affected immigrants from all nations. An 1882 law made each immigrant pay a tax and barred criminals from entering the country. In 1897, Congress passed a bill requiring immigrants to be able to read and write in some language. Although President Cleveland vetoed the bill as unfair, Congress later passed the Immigration Act of 1917, which included a similar literacy requirement.

Despite some anti-immigrant sentiment, many Americans, including Grace Abbott and Julia Clifford Lathrop, who helped found the Immigrants’ Protective League, spoke out in support of immigration. These Americans recognized that the United States was a nation of immigrants and that the newcomers made lasting contributions to their new society.