During the first 30 years of the 1800s, American industry was truly born. Household manufacturing was almost universal in colonial days with local craftsmen providing for their communities. This new era introduced factories with machines and predetermined tasks that produced items to be shipped and sold elsewhere. Canal and railway construction played an important role in transporting people and cargo West, increasing the size of the U.S. marketplace. With the new infrastructure, even remote parts of the country gained the ability to communicate and establish trade relationships with the centers of commerce in the East.

Read the following information and take notes on the new canal and railroad systems in America and their importance.

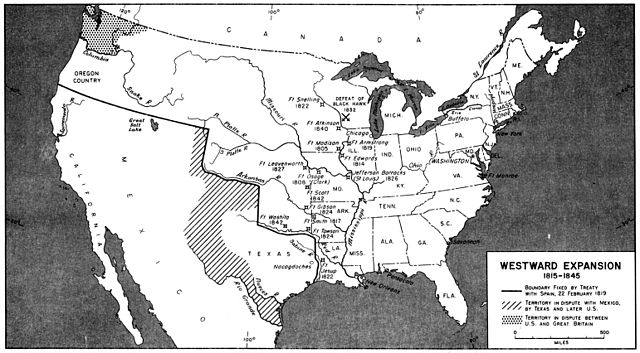

Westward expansion of the United States, 1815 to 1845

Americans moved westward in waves. The first wave began before the 1790s and led to the admission of four new states between 1791 and 1803: Vermont, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio. A second wave of westward growth began between 1816 and 1821. Five new western states were created: Indiana, Illinois, Mississippi, Alabama, and Missouri. The new states reflected the dramatic growth of the region west of the Appalachians. Ohio, for example, had only 45,000 settlers in 1800. By 1820, it had 581,000.

Pioneer families tended to settle in communities along the great rivers, such as the Ohio and the Mississippi, so that they could ship their crops to market. The expansion of canals, which crisscrossed the land in the 1820s and 1830s, allowed people to live farther away from the rivers. People also tended to settle with others from their home communities. Indiana, for example, was settled mainly by people from Kentucky and Tennessee, while Michigan’s pioneers came mostly from New England.

A replica of the Clermont steamboat; the original debuted in 1807.

River travel had definite advantages over wagon and horse travel. It was far more comfortable than travel over the bumpy roads, and pioneers could load all their goods on river barges, if they were heading downstream in the direction of the current. River travel had two problems, however. The first related to the geography of the eastern United States. Most major rivers in the region flowed in a north-south direction, not east to west, where most people and goods were headed. Second, traveling upstream by barge against the current was extremely difficult and slow.

Steam engines were already being used in the 1780s and 1790s to power boats in quiet waters. Inventor James Rumsey equipped a small boat on the Potomac River with a steam engine. John Fitch, another inventor, built a steamboat that navigated the Delaware River. Neither boat, however, had enough power to withstand the strong currents and winds found in large rivers or open bodies of water. In 1802, Robert Livingston, a political and business leader, hired Robert Fulton to develop a steamboat with a powerful engine. Livingston wanted the steamboat to carry cargo and passengers up the Hudson River from New York City to Albany.

In 1807, Fulton had his steamboat, the Clermont, ready for a trial. Powered by a newly designed engine, the Clermont made the 150-mile trip from New York to Albany in the unheard-of time of 32 hours. Using only sails, the trip would have taken four days. About 140-feet long and 14-feet wide, the Clermont offered great comforts to its passengers. They could sit or stroll about on deck, and at night they could relax in the sleeping compartments below deck. The engine was noisy, but its power provided a smooth ride. Steamboats ushered in a new age in river travel. They greatly improved the transport of goods and passengers along major inland rivers. Shipping goods became cheaper and faster. Steamboats also contributed to the growth of river cities like Cincinnati and St. Louis.

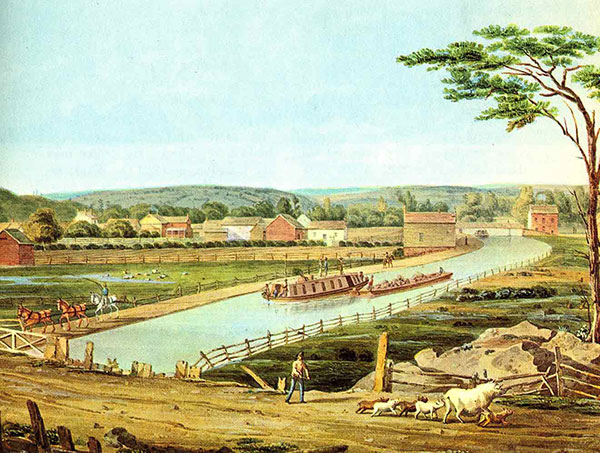

A barge passes through the Erie Canal at Little Falls, New York, circa 1890. Photo by William Henry Jackson.

Traveling west was not easy in the late 1790s and early 1800s. For example, the 363-mile trip from New York City to Buffalo, New York could take as long as three weeks. Although steamboats represented a great improvement in transportation, their routes depended on the existing river system. Steamboats could not effectively tie the eastern and western parts of the country together. In New York, business and government officials led by De Witt Clinton came up with a plan to link New York City with the Great Lakes region. They would build a canal, an artificial waterway, across New York State, connecting Albany on the Hudson River with Buffalo on Lake Erie.

Thousands of laborers, many of them Irish immigrants, worked on the construction of the 363-mile Erie Canal. Along the canal they built a series of locks, or separate compartments where water levels were raised or lowered. Locks provided a way to raise and lower boats at places where canal levels changed. After more than two years of digging, the Erie Canal opened on October 26, 1825. Clinton boarded a barge in Buffalo and journeyed on the canal to Albany. From there, he headed down the Hudson River to New York City. As crowds cheered, the officials poured water from Lake Erie into the Atlantic. The East and Midwest were joined.

In its early years, the canal did not allow steamboats because their powerful engines could damage the earthen embankments along the canal. Instead, teams of mules or horses hauled the boats and barges. A two-horse team pulled a 100-ton barge about 24 miles in one day, astonishingly fast compared to travel by wagon. In the 1840s, the canal banks were reinforced to accommodate steam tugboats pulling barges. The success of the Erie Canal led to an explosion in canal building. By 1850 the United States had more than 3,600 miles of canals. Canals lowered the cost of shipping goods. They brought prosperity to the towns along their routes. Perhaps most important, they helped unite the growing country.

An 1800s-era steam engine

The development of railroads in the United States began with short stretches of tracks that connected mines with nearby rivers. Early trains were pulled by horses rather than by locomotives. The first steam-powered passenger locomotive, the Rocket, began operating in Britain in 1829. Peter Cooper designed and built the first American steam locomotive in 1830. Called the Tom Thumb, it got off to a bad start. In a race against a horse-drawn train in Baltimore, the Tom Thumb’s engine failed. Engineers soon improved the engine, and within 10 years steam locomotives were pulling trains in the United States.

In 1840, the United States had almost 3,000 miles of railroad track. By 1860, it had almost 31,000 miles, mostly in the North and the Midwest. One railway linked New York City and Buffalo. Another connected Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Yet another linked Baltimore with Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia). Railway builders connected these eastern lines to lines being built farther west in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. By 1860, a network of railroad track would unite the Midwest and the East.

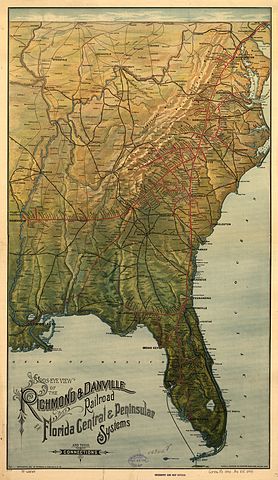

An 1893 map of the Florida Central and Peninsular Railroad and Richmond and Danville Railroad

Along with canals, the railways transformed trade in the nation’s interior. The changes began with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and the first railroads of the 1830s. Before this time, agricultural goods were carried down the Mississippi River to New Orleans and then shipped to other countries or to the East Coast of the United States.

The development of the east-west canal and the rail network allowed grain, livestock, and dairy products to move directly from the Midwest to the East. Because goods now traveled faster and more cheaply, manufacturers in the East could offer them at lower prices. The railroads also played an important role in the settlement and industrialization of the Midwest. Fast, affordable train travel brought people into Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. As the populations of these states grew, new towns and industries developed.

Natural waterways provided the chief means for transporting goods in the South. Most towns were located on the seacoast or along rivers. There were few canals, and roads were poor. Like the North, the South also built railroads, but to a lesser extent. Southern rail lines were short, local, and did not connect all parts of the region in a network. As a result, Southern cities grew more slowly than cities in the North and Midwest, where railways provided the major routes of commerce and settlement. By 1860, only about one-third of the nation’s rail lines lay within the South.