Throughout the 1800s, people in different areas of the country felt differently about issues, such as slavery and industrialization. As the country grew, the industrial North, the agricultural South, and the Western frontier had different economies and different needs. Political differences began to emerge as politicians favored one issue over another.

In 1890, Missouri issued a proclamation to Congress to become part of the Union as a slave state. At the time, the Union had 11 free states and 11 slave states. Congress did not want the slave states to have the majority in Congress. To protect the free states, the house passed a special amendment. It declared that the United States would accept Missouri as a slave state, but importing enslaved Africans would be illegal. It also set free the children of the Missouri slaves.

Read the following information on the specifics of the Missouri Compromise.

In the early 1800s, sectionalism became more intense as differences arose over national policies.

The Era of Good Feelings did not last long. Regional differences soon came to the surface, ending the period of national harmony. Most Americans felt a strong allegiance to the region where they lived. They thought of themselves as Westerners or Southerners or Northerners. This sectionalism, or loyalty to their region, became more intense as differences arose over national policies. The conflict over slavery, for example, had always simmered beneath the surface. Most white Southerners believed in the necessity and value of slavery while Northerners were increasingly opposed it. To protect slavery, Southerners stressed the importance of states’ rights. States’ rights are provided in the Constitution. Southerners believed they had to defend these rights against the federal government infringing on them.

The different regions also disagreed on the need for tariffs, a national bank, and internal improvements. Internal improvements were federal, state, and privately funded projects, such as canals and roads, to develop the nation’s transportation system. Three powerful voices emerged in Congress in the early 1800s as spokespersons for their regions: John C. Calhoun, Daniel Webster, and Henry Clay.

A portrait of John C. Calhoun

A portrait of Daniel Webster

John C. Calhoun, a planter from South Carolina, was one of the War Hawks who had called for war with Great Britain in 1812. Calhoun remained a nationalist for some time after the war. He favored support for internal improvements and developing industries, and he backed a national bank. At the time, he believed these programs would benefit the South. In the 1820s, however, Calhoun’s views started to change, and he emerged as one of the chief supporters of state sovereignty, the idea that states have autonomous power. Calhoun became a strong opponent of nationalist programs such as high tariffs. Calhoun and other Southerners argued that tariffs raised the prices that they had to pay for the manufactured goods they could not produce for themselves. They also argued that high tariffs protected inefficient manufacturers.

First elected to Congress in 1812 to represent his native New Hampshire, Daniel Webster later represented Massachusetts in both the House and the Senate. Webster began his political career as a supporter of free trade and the shipping interests of New England. In time, Webster came to favor the Tariff of 1816, which protected American industries from foreign competition, and other policies that he thought would strengthen the nation and help the North. Webster gained fame as one of the greatest orators of his day. As a United States senator, he spoke eloquently in defense of the nation against sectional interests. In one memorable speech Webster declared, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”

Another leading War Hawk, Henry Clay of Kentucky, became Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1811 and a leader who represented the interests of the Western states. He also served as a member of the delegation that negotiated the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. Above all, Henry Clay became known as the national leader who tried to resolve sectional disputes through compromise.

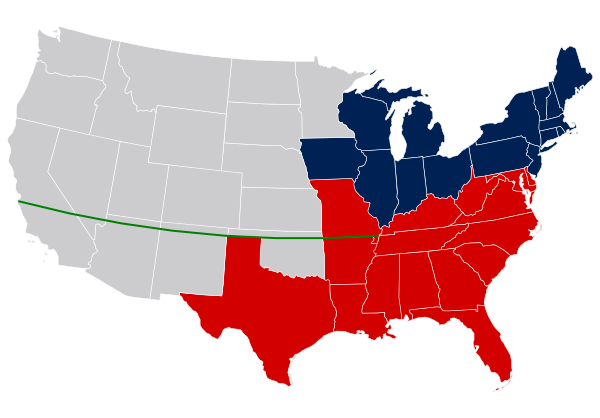

This map shows states' views on slavery as of 1850. The states that prohibited slavery are in blue, and the states that allowed it are in red. The green line represents the 36°30'N parallel, or the Missouri Compromise Line; slavery was banned in areas north of the line.

Sectional tension reached new heights in 1820 over the issue of admitting new states to the Union. The problem revolved around slavery. The South wanted Missouri, part of the Louisiana Purchase, admitted as a slave state. Northerners wanted Missouri to be free of slavery. The issue became the subject of debate throughout the country, exposing bitter regional divisions that would plague national politics for decades.

While Congress considered the Missouri question, Maine, still part of Massachusetts, also applied for statehood. The discussions about Missouri now broadened to include Maine. Some observers feared for the future of the Union. Eventually, Henry Clay helped work out a compromise that preserved the balance between North and South. The Missouri Compromise, reached in March 1820, provided for the admission of Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. The agreement banned slavery in the remainder of the Louisiana Territory north of the 36°30'N parallel.

An illustration of Henry Clay

Though he was a spokesperson for the West, Henry Clay believed his policies would benefit all sections of the nation. In an 1824 speech, the called his program the “American System.” The American System included a protective tariff; a program of internal improvements, especially the building of roads and canals, to stimulate trade; and a national bank to control inflation and to lend money to build developing industries.

Clay believed that the three parts of his plan would work together. The tariff would provide the government with money to build roads and canals. Healthy businesses could use their profits to buy more agricultural goods from the South, then ship these goods northward along the nation’s efficient new transportation system. Not everyone saw Clay’s program in such positive terms. Former president Jefferson believed the American System favored the wealthy manufacturing classes in New England. Many people in the South agreed with Jefferson. They saw no benefits to the South from the tariff or internal improvements. In the end, little of Clay’s American System went into effect. Congress eventually adopted some internal improvements, though not on the scale Clay had hoped for. Congress had created the Second National Bank in 1816, but it remained an object of controversy.

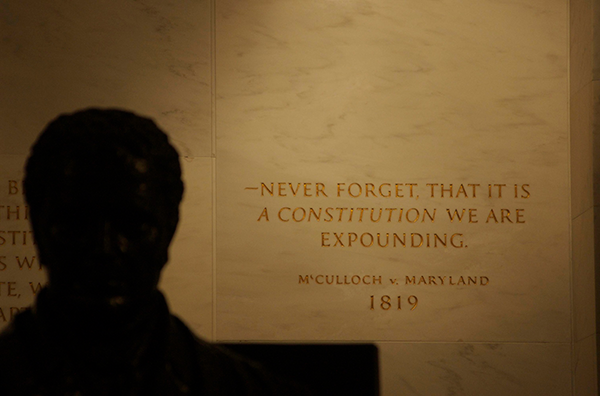

A statue of John Marshall in the foreground, with a quotation from McCulloch v. Maryland (written by Marshall) engraved into the wall, at the U.S. Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C.

The Supreme Court also became involved in sectional and states’ rights issues at this time. The state of Maryland imposed a tax on the Baltimore branch of the Second Bank of the United States, a federal institution. The Bank refused to pay the state tax, and the case, McCulloch v. Maryland, reached the Court in 1819. Speaking for the Court, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that Maryland had no right to tax the Bank because it was a federal institution. He argued that the Constitution and the federal government received their authority directly from the people, not by way of the state governments. Those who opposed the McCulloch decision argued that it was a “loose construction” of the Constitution, which says that the federal government can “coin” money, gold, silver, and other coins, but the Constitution does not mention paper money. In addition, the Constitutional Convention had voted not to give the federal government the authority to charter corporations, including banks.

Another Supreme Court case, Gibbons v. Ogden, established that states could not enact legislation that would interfere with Congressional power over interstate commerce. The Supreme Court’s rulings strengthened the national government. They also contributed to the debate over sectional issues. People who supported states’ rights believed that the decisions increased federal power at the expense of state power. Strong nationalists welcomed the rulings’ support for national power.