Read the information below about social changes in the United States. Take notes as you read.

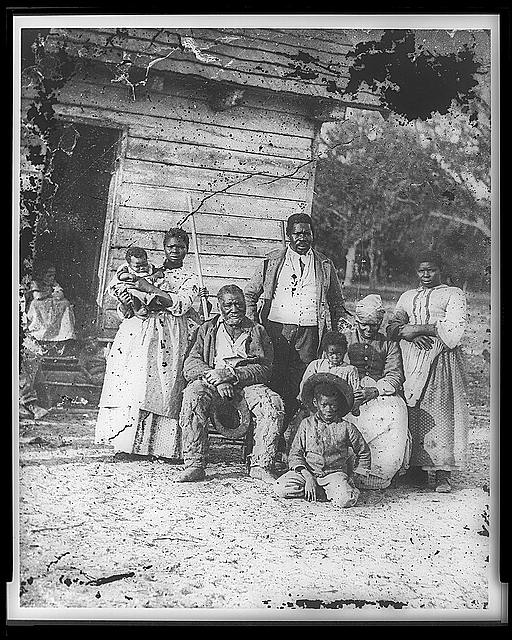

An 1800s log home on a farm

Popular novels and films often portray the South before 1860 as a land of stately plantations owned by rich white slaveholders. In reality, most white Southerners were either small farmers without slaves or planters with a handful of slaves. Only a few planters could afford the many enslaved Africans and the lavish mansions shown in fictional accounts of the Old South. Most white Southerners fit into one of four categories: yeomen, tenant farmers, the rural poor, or plantation owners.

The farmers who did not have slaves, yeomen, made up the largest group of whites in the South. Most yeomen owned land. Although they lived throughout the region, they were most numerous in the Upper South and in the hilly rural areas of the Deep South, where the land was unsuited to large plantations. A yeoman’s farm usually ranged from 50 to 200 acres. Yeomen grew crops both for their own use and to sell, and they often traded their produce to local merchants and workers for goods and services.

Most Southern whites did not live in elegant mansions or on large plantations. They lived in far simpler homes, though the structure of their homes changed over time. In the early 1800s many lived in cottages built of wood and plaster with thatched roofs. Later many lived in one-story frame houses or log cabins. Not all Southern whites owned land. Some rented land, or worked as tenant farmers, on landlords’ estates. Others, the rural poor, lived in crude cabins in wooded areas where they could clear a few trees, plant some corn, and keep a hog or a cow. They also fished and hunted for food. The poor people of the rural South were stubbornly independent. They refused to take any job that resembled the work of enslaved people. Although looked down on by other whites, the rural poor were proud of being self-sufficient.

Oak Alley Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana

A large plantation might cover several thousand acres. Well-to-do plantation owners usually lived in comfortable but not luxurious farmhouses. They measured their wealth partly by the number of enslaved people they controlled and partly by such possessions as homes, furnishings, and clothing. A small group of plantation owners, about 4 percent, held 20 or more slaves in 1860. Most slaveholders held fewer than 10 enslaved workers. A few free African Americans possessed slaves. The Metoyer family of Louisiana owned thousands of acres of land and more than 400 slaves. Most often, these slaveholders were free African Americans who purchased their own family members to free them.

The main economic goal for large plantation owners was to earn profits. Such plantations had fixed costs—regular expenses such as housing and feeding workers and maintaining cotton gins and other equipment. Fixed costs remained about the same year after year. Cotton prices, however, varied from season to season, depending on the market. To receive the best prices, planters sold their cotton to agents in cities such as New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, and Savannah. The cotton exchanges, or trade centers, in Southern cities were of vital importance to those involved in the cotton economy.

The agents of the exchanges extended credit—a form of loan—to the planters and held the cotton for several months until the price rose. Then the agents sold the cotton. This system kept the planters always in debt because they did not receive payment for their cotton until the agents sold it.

The wife of a plantation owner generally oversaw the enslaved workers who toiled in her home and tended to them when they became ill. Her responsibilities also included supervising the plantation’s buildings and the fruit and vegetable gardens. Some wives served as accountants, keeping the plantation’s financial records. Women often led a difficult and lonely life on the plantation. When plantation agriculture spread westward into Alabama and Mississippi, many planters’ wives felt they were moving into a hostile, uncivilized region. Planters traveled frequently to look at new land or to deal with agents in New Orleans or Memphis. Their wives spent long periods alone at the plantation. Plantation owners and those who could afford to do so often sent their children to private schools. One of the best known was the academy operated by Moses Waddel in Willington, South Carolina. Students attended six days a week. The Bible and classical literature were stressed, but the courses also included mathematics, religion, Greek, Latin, and public speaking.

A family of enslaved African Americans on Smith's Plantation in Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1862

Large plantations needed many kinds of workers. Some enslaved people worked in the house, cleaning, cooking, doing laundry, sewing, and serving meals. They were called domestic slaves. Other African Americans were trained as blacksmiths, carpenters, shoemakers, or weavers. Still others worked in the pastures, tending the horses, cows, sheep, and pigs. Most of the enslaved African Americans, however, were field hands. They worked from sunrise to sunset planting, cultivating, and picking cotton and other crops. They were supervised by an overseer, a plantation manager.

Enslaved African Americans endured hardship and misery. They worked hard, earned no money, and had little hope of freedom. One of their worst fears was being sold to another planter and separated from their loved ones. In the face of these brutal conditions, enslaved African Americans maintained their family life as best they could and developed a culture all their own. They resisted slavery through a variety of ingenious methods, and they looked to the day when they would be liberated.

Enslaved people had few comforts beyond the bare necessities. The often lived in log huts with bare dirt floors. They only shared one room with dozens crammed into them. Beds were just straw or old rags. Enslaved people faced constant uncertainty and danger. American law in the early 1800s did not protect enslaved families. At any given time, a husband or wife could be sold away, or a slaveholder’s death could lead to the breakup of an enslaved family. Although marriage between enslaved people was not recognized by law, many couples did marry. To provide some measure of stability in their lives, enslaved African Americans established a network of relatives and friends, who made up their extended family. If a father or mother were sold away, an aunt, uncle, or close friend could raise the children left behind. Large, close-knit extended families became a vital feature of African American culture.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Enslaved African Americans endured their hardships by extending their own culture, fellowship, and community. They fused African and American elements into a new culture. The growth of the African American population came mainly from children born in the United States. In 1808, Congress outlawed the slave trade. Although slavery remained legal in the South, no new slaves could enter the United States. By 1860, almost all the enslaved people in the South had been born there. These native-born African Americans held on to their African customs. They continued to practice African music and dance. They passed traditional African folk stories to their children. Some wrapped colored cloths around their heads in the African style.

Although many enslaved African Americans accepted Christianity, they often followed the religious beliefs and practices of their African ancestors as well. For many enslaved African Americans, Christianity became a religion of hope and resistance. They prayed fervently for the day when they would be free from bondage. The passionate beliefs of the Southern slaves found expression in the spiritual, an African American religious folk song. Spirituals provided a way for the enslaved African Americans to communicate secretly among themselves. Many spirituals combined Christian faith with laments about earthly suffering.

This engraving from William Still's 1872 book The Underground Railroad depicts fugitive slaves arriving in Philadelphia along the banks of the Schuylkill River in July 1856.

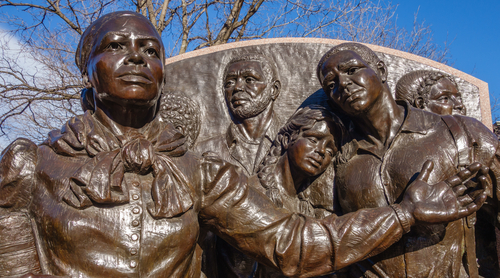

A close-up of a statue honoring Harriet Tubman in Boston

Between 1830 and 1860, life under slavery became even more difficult because the slave codes, the laws in the Southern states that controlled enslaved people, became more severe. In existence since the 1700s, slave codes aimed to prevent the event white Southerners dreaded most: slave rebellion. For this reason, slave codes prohibited slaves from assembling in large groups and from leaving their master’s property without a written pass. Slave codes also made it a crime to teach enslaved people to read or write. White Southerners feared that a literate slave might lead other African Americans in rebellion. A slave who did not know how to read and write, whites believed, was less likely to rebel.

Some enslaved African Americans did rebel openly against their masters. One was Nat Turner, a popular religious leader among his fellow slaves. Turner had taught himself to read and write. In 1831, Turner led a group of followers on a brief, violent rampage in Southhampton County, Virginia. Before being captured Turner and his followers killed at least 55 whites. Nat Turner was hanged, but his rebellion frightened white Southerners and led them to pass more severe slave codes. Armed rebellions were rare, however. African Americans in the South knew that they would only lose in an armed uprising. For the most part enslaved people resisted slavery by working slowly or by pretending to be ill. Occasionally resistance took more active forms, such as setting fire to a plantation building or breaking tools. Resistance helped enslaved African Americans endure their lives by striking back at white masters—and perhaps establishing boundaries that white people would respect.

Some enslaved African Americans tried to run away to the North and a few succeeded. Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, two African American leaders who were born into slavery, gained their freedom when they fled to the North. Yet for most enslaved people, getting to the North was almost impossible, especially from the Deep South. Most slaves who succeeded in running away escaped from the Upper South. The Underground Railroad, a network of “safe houses” owned by free blacks and whites who opposed slavery, offered assistance to runaway slaves. Some slaves ran away to find relatives on nearby plantations or to escape punishment. Rarely did they plan to make a run for the North. Most runaways were captured and returned to their owners. Discipline was severe; the most common punishment was whipping.

Atlanta, Georgia, around 1862-1865

Although the South was primarily agricultural, it was the site of several large cities by the mid-1800s. By 1860, the population of Baltimore had reached 212,000 and the population of New Orleans had reached 168,000. The ten largest cities in the South were either seaports or river ports. With the coming of the railroad, many other cities began to grow as centers of trade. Among the cities located at the crossroads of the railways were Columbia, South Carolina; Chattanooga, Tennessee; Montgomery, Alabama; Jackson, Mississippi; and Atlanta, Georgia. The population of Southern cities included white city dwellers, some enslaved workers, and many of the South’s free African Americans.

The cities provided free African Americans with opportunities to form their own communities. African American barbers, carpenters, and small traders offered their services throughout their communities. Free African Americans founded their own churches and institutions. In New Orleans they formed an opera company. Although some free African Americans prospered in the cities, their lives were far from secure. Between 1830 and 1860, Southern states passed laws that limited the rights of free African Americans. Most states would not allow them to migrate from other states. Although spared the horrors of slavery, free African Americans were denied an equal share in economic and political life.

Review what you have learned in the activity below.

How did enslaved people resist slavery? How did resistance help enslaved people?

How did the lack of capital become a stumbling block to the growth of industry in the South?

How did the factory system change the way Americans worked?

| Your Responses | Sample Answers |

|---|---|

| Enslaved people resisted slavery by working slowly or by pretending to be sick. Sometimes resistance took more active forms, such as setting fire to plantation buildings or breaking tools. Armed rebellions were rare. Resistance helped African Americans endure their lives by striking back at white plantation owners—perhaps establishing boundaries that white people would respect. | |

| To develop industries required money, but many Southerners had their wealth invested in land and slaves. Most wealthy Southerners were unwilling to do this. They believed that an economy based on cotton would continue to prosper and saw no need to risk their resources in new industrial ventures. | |

| Many Americans moved from farms to the cities during the 1800s as factories provided more and more jobs. As the factory system developed, working conditions worsened. Factory owners wanted their employees to work longer hours to produce more goods. By 1840, the average workday was 11.4 hours long. Injuries, such as lost fingers and broken bones, were common. Women and children joined the workforce. | |