Throughout the 19th century, immigrants from Europe came to America in waves. Mostly these immigrants came from Ireland and Germany. These men, women, and children came to America for many reasons, including because of civil strife, religious unrest, unemployment, and famine. The immigrants would become part of the American culture. Many Americans today are descendents of European immigrants who came to the United States in search of a better life.

Read the following information about Irish and German immigrants. Take notes as you read.

Irish immigrants disembarking in New York in 1855.

Immigration, movement of people into a country, to the United States increased dramatically between 1840 and 1860. American manufacturers welcomed the tide of immigrants, many of whom were willing to work for long hours and for low pay. The largest group of immigrants to the United States at this time traveled across the Atlantic from Ireland. Between 1846 and 1860, more than 1.5 million Irish immigrants arrived in the country, settling mostly in the Northeast.

The Irish migration to the United States was brought on by a terrible potato famine. Potatoes were the main part of the Irish diet. When a devastating blight, or disease, destroyed Irish potato crops in the 1840s, starvation struck the country, resulting a in a famine. More than one million people died. Although most of the immigrants had been farmers in Ireland, they were too poor to buy land in the United States. For this reason, many Irish immigrants took low-paying factory jobs in Northern cities. The men who came from Ireland worked in factories or performed manual labor, such as working on the railroads. The women, who accounted for almost half of the immigrants, became servants and factory workers.

The second-largest group of immigrants in the United States between 1820 and 1860 came from Germany. Some sought work and opportunity. Others had left their homes because of the failure of a democratic revolution in Germany in 1848. Between 1848 and 1860, more than one million German immigrants, many in family groups, settled in the United States. Many arrived with enough money to buy farms or open their own businesses. They prospered in many parts of the country, founding their own communities and self-help organizations. Some German immigrants settled in New York and Pennsylvania, but many moved to the Midwest and the western territories.

A traditional German accordion

The immigrants who came to the United States between 1820 and 1860 changed the character of the country. These people brought their languages, customs, religions, and ways of life with them, some of which filtered into American culture. Before the early 1800s, most immigrants to America had been either Protestants from Great Britain or Africans brought forcibly to America as slaves. At the time, the country had relatively few Catholics, and most of these lived around Baltimore, New Orleans, and St. Augustine. Most of the Irish immigrants and about one-half of the German immigrants were Roman Catholics.

Many Catholic immigrants settled in cities of the Northeast. The Church gave the newcomers more than a source of spiritual guidance. It also provided a center for the community life of the immigrants. The German immigrants brought their language as well as their religion. When they settled, they lived in their own communities, founded German-language publications, and established musical societies. Many Germans were Catholic, especially those from the southern regions, such as Bavaria. Other Germans were Lutheran, which was also a minority faith in America compared to other Protestant groups. This is the reason for the cultural aspects of the northern Midwest today.

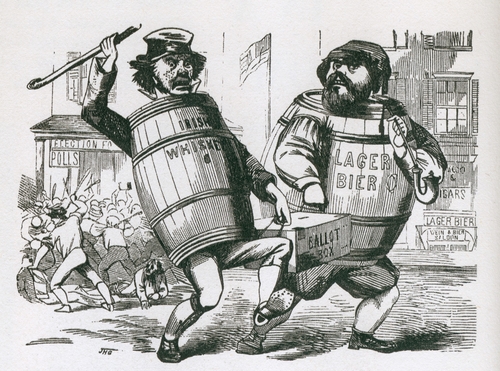

An anti-immigrant cartoon from around 1850 shows two men with barrels as bodies, labeled "Irish Whiskey" and "Lager Bier," carrying a ballot box.

In the 1830s and 1840s, anti-immigrant feelings rose. Some Americans feared that immigrants were changing the character of the United States too much. People opposed to immigration were known as nativists because they felt that immigration threatened the future of “native” American-born citizens. Some nativists accused immigrants of taking jobs from “real” Americans and were angry that immigrants would work for lower wages. Others accused the newcomers of bringing crime and disease to American cities. Immigrants who lived in crowded slums served as likely targets of this kind of prejudice.

There was also a strong undercurrent of anti-Catholic feeling among nativists. Protestants in America often held on to the same feelings about Catholicism that their British ancestors had. As well, there was fear that Catholics would follow the orders of the pope and Catholic monarchs in Europe to end American democracy. This was often encouraged by scandalous stories printed by nativist authors that told false stories about Catholic clergy and nuns. The nativists formed secret anti-Catholic societies, and in the 1850s, they joined to form a new political party: the American Party. Because members of nativist groups often answered questions about their organization with the statement “I know nothing,” their party came to be known as the Know-Nothing Party. The Know-Nothings called for stricter citizenship laws, extending the immigrants’ waiting period for citizenship from 5 to 21 years, and wanted to ban foreign-born citizens from holding office. In the mid-1850s, the Know-Nothing movement split into a Northern branch and a Southern branch over the question of slavery. At that time, the slavery issue was also dividing the Northern and Southern states of the nation.