In 1800, Sacajawea, aged 12, and a member of the Shoshone tribe in Idaho, was kidnapped by warriors from the Hidasta Sioux and taken to North Dakota. The next year, a French trader named Toussaint Charbonneau either purchased her or won her gambling; then he married her.

At 16 years old and a recent mother, she became a member of Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery. Able to speak Shoshone, the explorers knew they would meet up with the tribe and needed someone to interpret.

Both Lewis and Clark called her "indispensable" to the party. She helped the Corps by digging roots and other types of foods, showing the men how to make leather clothes and moccasins, and saving important journal papers from a capsized canoe.

As the Corps traveled west, she recognized many landmarks from her home in the area around Three Forks, Idaho. Meriwether Lewis and a small party of his men made the first contact with the Shoshone. They eventually met Chief Camehawait and tried to bargain for horses and guides to get over the Rocky Mountains. When Clark and the rest of the expedition caught up with them, Camehawait and Sacajawea recognized each other--they were brother and sister.

Sacajawea was instrumental in translating for Lewis and Clark, bartering for horses, and getting Shoshone guides to lead them over the Rocky Mountains. The expedition was successful in reaching the Pacific Ocean. On the return home, Sacajawea was able to suggest an alternate route through the Rockies because of her earlier experience.

In addition to the services she provided to the Corps as interpreter, forager, and guide, her presence made tribes encountered by the expedition less suspicious. They knew that a war party would not have a female traveling with them.

She returned to North Dakota and died at the age of 25. Dozens of monuments are dedicated to her, and many places have been named after her. In 2000, the U.S. Mint issued the Sacajawea coin in her honor.

Read the following information and take notes about the expedition of Lewis and Clark.

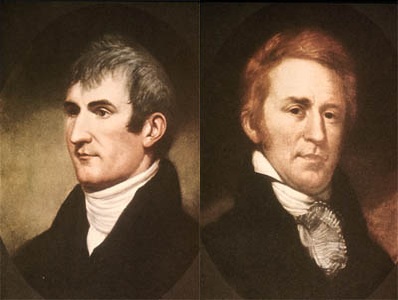

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

Jefferson wanted to know more about the mysterious lands west of the Mississippi. Even before the Louisiana Purchase was complete, he persuaded Congress to sponsor an expedition to explore the new territory. Jefferson was particularly interested in the expedition as a scientific venture. Congress was interested in commercial possibilities and in sites for future forts.

To head the expedition, Jefferson chose his private secretary, 28-year-old Meriwether Lewis. Lewis was well qualified to lead this journey of exploration. He had joined the militia during the Whiskey Rebellion and had been in the army since that time. The expedition’s co-leader was William Clark, 32, a friend of Lewis’s from military service. Both Lewis and Clark were knowledgeable amateur scientists and had conducted business with Native Americans. Together they assembled a crew that included expert river men, gunsmiths, carpenters, scouts, and a cook. Two men of mixed Native American and French heritage served as interpreters. An African American named York rounded out the group.

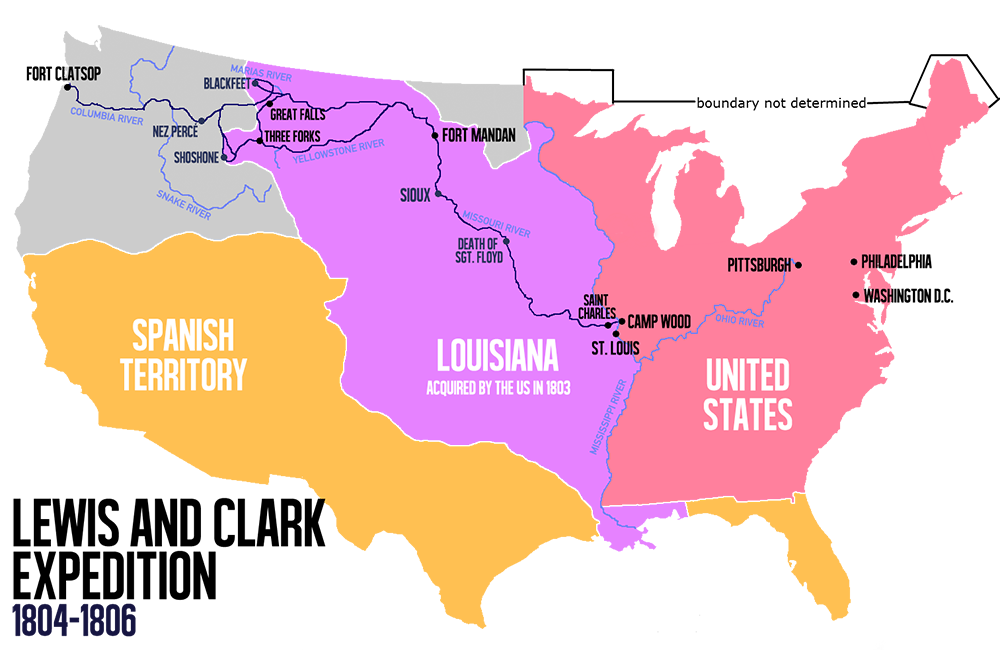

The expedition left St. Louis in the spring of 1804 and slowly worked its way up the Missouri River. Lewis and Clark kept a journal of their voyage and made notes on what they saw and did. Along their journey, they encountered Native American groups. One young Shoshone woman named Sacagawea joined their group as a guide. After 18 months and nearly 4,000 miles, Lewis and Clark reached the Pacific Ocean. After spending the winter there, both explorers headed back east along separate routes.

When the expedition returned in September 1806, it had collected valuable information on people, plants, animals, and the geography of the West. Perhaps most important, the journey provided inspiration to a nation of people eager to move westward. Even before Lewis and Clark returned, Jefferson sent others to explore the wilderness. Lieutenant Zebulon Pike led two expeditions between 1805 and 1807, traveling through the upper Mississippi River valley and into the region that is now the state of Colorado. In Colorado, he found a snow-capped mountain he called Grand Peak. Today this mountain is known as Pike’s Peak. During his expedition, Pike was captured by the Spanish but was eventually released.

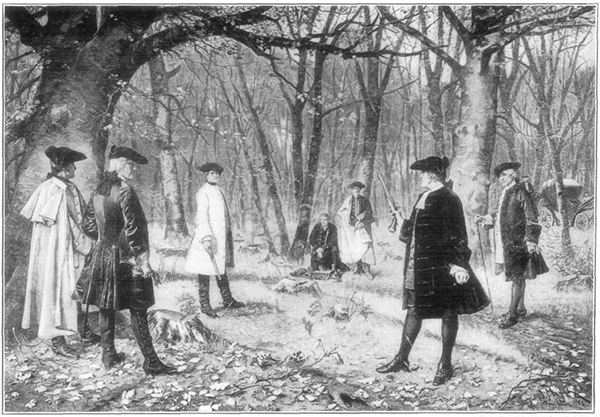

Illustration, Duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, after the painting by J. Mund. The duel took place in Weehawken, New Jersey, on July 11, 1804.

Many Federalists opposed the Louisiana Purchase. They feared that the states carved out of the new territory would become Republican, reducing the Federalists’ power. A group of Federalists in Massachusetts plotted to secede, or withdraw, from the Union. They wanted New England to form a separate “Northern Confederacy.” The plotters realized that to have any chance of success, the Northern Confederacy would have to include New York as well as New England. The Massachusetts Federalists needed a powerful friend in that state who would back their plan. They turned to Aaron Burr, who had been cast aside by the Republicans for his refusal to withdraw from the 1800 election. The Federalists gave Burr their support in 1804, when he ran for governor of New York.

Alexander Hamilton had never trusted Aaron Burr. Now, Hamilton was concerned about rumors that Burr had secretly agreed to lead New York out of the Union. Hamilton accused Burr of plotting treason. When Burr lost the election for governor, he blamed Hamilton and challenged him to a duel. In July 1804, the two men, armed with pistols, met in Weehawken, New Jersey. Hamilton hated dueling and pledged not to shoot at his rival. Burr, however, did fire and aimed to hit Hamilton. Seriously wounded, Hamilton died the next day. Burr fled to avoid arrest.

Riding the wave of four successful years as president, Jefferson won reelection easily in 1804. Jefferson received 162 electoral votes to only 14 for his Federalist opponent, Charles Pinckney. His second term began with the nation at peace.

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.