The War of 1812 was instrumental in American history for a number of reasons, but it also brought an end to the Federalists party in America. Thomas Jefferson was such a strong figure in bringing America together that people were disillusioned with the Federalists party which tried to stop Jefferson at every step of the way.

Read the information below about the end of the Federalists party and the Era of Good Feelings. Take notes as you read.

This portrait of President James Monroe was painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1817.

The absence of major political divisions after the War of 1812 helped forge a sense of national unity, and the Federalist Party all but destroyed. In the 1816 presidential election, another Virginian named James Monroe, the Republican candidate, faced almost no opposition. The Federalists, weakened by doubts of their loyalty during the War of 1812, barely existed as a national party. Monroe won the election by an overwhelming margin. Although the Federalist Party had almost disappeared, many of its programs gained support. Republican president James Madison, Monroe’s predecessor, had called for tariffs to protect industries, for a national bank, and for other programs.

Political differences seemed to fade away, causing a Boston newspaper to call these years the Era of Good Feelings. The president himself symbolized these good feelings. Monroe had been involved in national politics since the American Revolution. He wore breeches and powdered wigs, a style no longer in fashion. With his sense of dignity, Monroe represented a united America, free of political strife. Early in his presidency, Monroe toured the nation. No president since George Washington had done this. He paid his own expenses and tried to travel without an official escort. Everywhere Monroe went, local officials greeted him and celebrated his visit.

Monroe arrived in Boston, the former Federalist stronghold, in the summer of 1817. About 40,000 well-wishers cheered him, and John Adams, the second president, invited Monroe to his home. Abigail Adams commended the new president’s “unassuming manner.” Monroe did not think the demonstrations were meant for him personally. He wrote Madison that they revealed a “desire in the body of the people to show their attachment to the union.” Two years later Monroe continued his tour, traveling as far south as Savannah and as far west as Detroit. The 1818 Congressional election brought another landslide victory for the Republicans, who controlled 85 percent of the seats in the U.S. Congress. In 1820, Monroe won reelection, winning all but one electoral vote. It seemed as if the old first party system was dead.

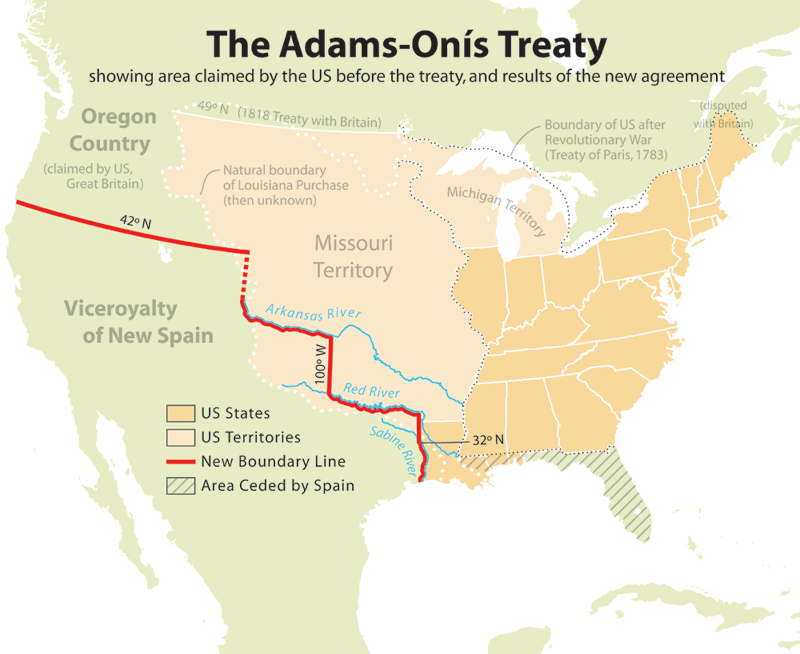

This map shows the area claimed by the U.S. before and after the Adams-Onís Treaty.

In the years following the War of 1812, Monroe and his secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, moved to resolve long-standing disputes with Great Britain and Spain. In 1817, in the Rush-Bagot Treaty, the United States and Britain agreed to set limits on the number of naval vessels each could have on the Great Lakes. The treaty provided for the disarmament, or the removal of weapons, along an important part of the border between the United States and British Canada. The second agreement with Britain, the Convention of 1818, set the boundary of the Louisiana Territory between the United States and Canada at the 49th parallel. The convention created a secure and demilitarized border, a border without armed forces. Through Adams’s efforts, Americans also gained the right to settle in the Oregon Country.

Meanwhile, Spain owned East Florida and claimed West Florida. The United States argued that West Florida was part of the Louisiana Purchase. In 1810 and 1812, Americans simply added parts of West Florida to Louisiana and Mississippi. Spain objected but took no action. In April 1818, General Andrew Jackson invaded Spanish East Florida, seizing control of two Spanish forts. Jackson had been ordered to stop Seminole raids on American territory from Florida. In capturing the Spanish forts, however, Jackson went beyond his instructions.

Luis de Onís, the Spanish minister to the United States, protested forcefully and demanded the punishment of Jackson and his officers. Secretary of War Calhoun said that Jackson should be court-martialed, or tried by a military court, for overstepping instructions. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams disagreed. Although Secretary of State Adams had not authorized Jackson’s raid, he did nothing to stop it. Adams guessed that the Spanish did not want war and that they might be ready to settle the Florida dispute. He was right. For the Spanish, the raid had demonstrated the military strength of the United States.

Already troubled by rebellions in Mexico and South America, Spain signed the Adams-Onís Treaty in 1819. Spain gave East Florida to the United States and abandoned all claims to West Florida. In return the United States gave up its claims to Spanish Texas and took over responsibility for paying the $5 million that American citizens claimed Spain owed them for damages. The two countries also agreed on a border between the United States and Spanish possessions in the West. The border extended northwest from the Gulf of Mexico to the 42nd parallel and then west to the Pacific, giving the United States a large piece of territory in the Pacific Northwest. America had become a transcontinental power.

A coin commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine

While the Spanish were settling territorial disputes with the United States, they faced a series of challenges within their empire. In the early 1800s, Spain controlled a vast colonial empire that included what is now the southwestern United States, Mexico and Central America, and all of South America except Brazil. In the fall of 1810 a priest, Miguel Hidalgo, led a rebellion against the Spanish government of Mexico. Hidalgo called for racial equality and the redistribution of land. The Spanish defeated the revolutionary forces and executed Hidalgo. In 1821, Mexico gained its independence, but independence did not bring social and economic change.

Independence in South America came largely as a result of the efforts of two men. Simón Bolívar, also known as “the Liberator,” led the movement that won freedom for the present-day countries of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Bolivia, and Ecuador. José de San Martín successfully achieved independence for Chile and Peru. By 1824, the revolutionaries’ military victory was complete, and most of South America had liberated itself from Spain. Portugal’s large colony of Brazil gained its independence peacefully in 1822. Spain’s empire in the Americas had shrunk to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and a few other islands in the Caribbean.

In 1822 Spain had asked France, Austria, Russia, and Prussia for help in its fight against revolutionary forces in South America. The possibility of increased European involvement in North America led Monroe to act. The president issued a statement, later known as the Monroe Doctrine, on December 2, 1823. While the United States would not interfere with any existing European colonies in the Americas, Monroe declared, it would oppose any new ones. North and South America “are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.” In 1823, the United States did not have the military power to enforce the Monroe Doctrine. The Monroe Doctrine nevertheless became an important element in American foreign policy and has remained so for more than 170 years.

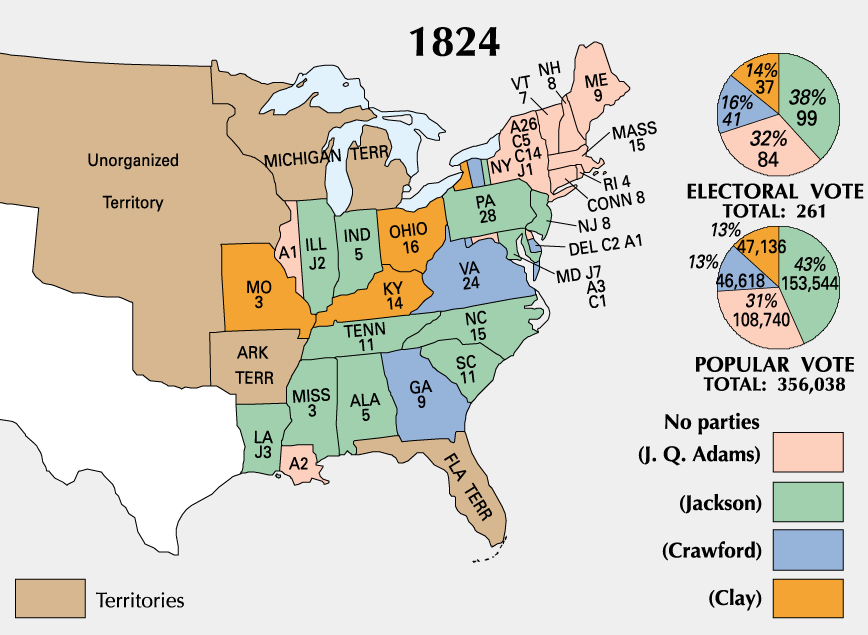

This map shows the votes of the Electoral College in the 1824 presidential election

Even though America had become a one-party system in peacetime, it was only on the surface. The Republicans, whose name was evolving to Democratic-Republicans, were not as united it as it seemed. Party leaders had tried to blend the ideas of Jefferson with the major economic policies of the late Alexander Hamilton – two completely opposite viewpoints. Monroe simply continued Madison’s polices. Jefferson had let the First Bank of the United States die during his administration. A second bank, proposed in 1816, would renew every major concern he had with the first, including direct competition with state banks. Also based in Philadelphia, it showed how much of the old Federalist economic agenda the Democratic-Republicans now supported. Jeffersonian ideas would oppose such a plan, but party leaders saw the need in order to build infrastructure. Andrew Jackson, who would serve as president in coming years, would eventually kill it, much as Jefferson had the first one.

The Era of Good Feelings could only last for so long. By the end of Monroe’s second term, the party was about ready to tear itself apart, somewhat based on regional lines. However, the cooperation of the era had created a new system where political parties played the crucial role building broad and lasting coalitions among diverse groups in the American public. These parties tried to represent more than the distinct interests of a single region or economic class, even if sectionalism would eventually develop. Most importantly, modern parties broke from a political tradition favoring personal loyalty and patronage.

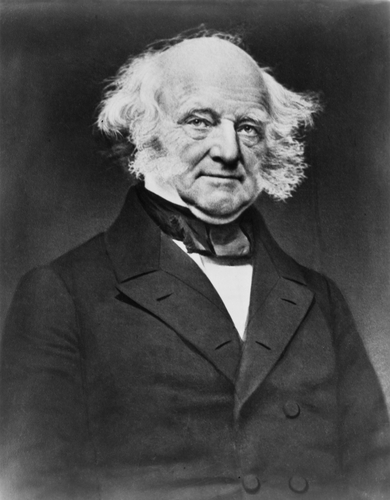

President Martin Van Buren

A new party system would emerge, however. A New York politician named Martin Van Buren played a key role in the development of the Second Party System. Not loyal to one single ideology, he broke from his Democratic-Republican party leadership to lead a new internal group who chose to just refer themselves as Democrats. By 1821, he helped create the system on a national scale while serving in Washington, D.C. as a senator.

As Monroe’s second term ended, one party still was in existence, but it was fracturing – once again on Jeffersonian and Hamiltonian lines, the old Republican and Federalist camps. This would lead to tension and scandal in the elections of John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. However, Van Buren was still leading the charge in how American politics would work. He responded to the growing democratization of American life in the first decades of the 19th century by embracing mass public opinion. Rather than follow a model of elite political leadership like that of the Founding Fathers, Van Buren saw "genius" in reaching out to the "multitude" of the general public, the Common Man. This would be key in the eventual election of the Jackson-Van Buren ticket.

Van Buren made careful use of newspapers to spread the word about party positions and to ensure close discipline among party members. In fact, the growth of newspapers in the new nation was closely linked to the rise of a competitive party system. Rather than make any claim to objective reporting, newspapers existed as propaganda machines for the political parties that they supported. Newspapers were especially important to the new party system because they spread information about the party platform, the set of party beliefs and policies. Eventually, though, Van Buren’s methods would lead of the rise of a minor party, the Whigs, which took in all the former Federalists. By the 1840s, America was a solidly two-party system once again.

| Which Democratic-Republican became president in 1818? | James Monroe |

| What was the period of one-party dominance called after the decline of the Federalists? | the Era of Good Feelings |

| What was established in 1816 that maintained elements of Hamilton and the Federalists? | the Second Bank of the United States |

| What party was newly established by Martin Van Buren? | the New Democratic party |

| What served as propaganda vehicles for the new political parties? | newspapers |