The year 1920 ushered in a decade in the U.S. called the "Roaring Twenties." It was an era of excessive celebration, endless innovation, and cultural revolution. The word roaring refers to the loud, exciting, and novel events of the time. People earned more money and had more leisure time, and social and cultural life in America changed as fast as the Ford Racer 999 could zoom around a track.

Henry Ford's Model T automobiles were being manufactured at a rapid rate and at a price that most working people could afford, as long as they didn't mind the only color it came in--black. Along with the automobile came highways, motels, diners, traffic jams, traffic lights, and gas stations.

Other inventions of the 1920s included frozen food, the first robot, and TV, not to mention such cultural icons as the yo-yo, Band-Aid, Kool-Aid, Pez, and bubble gum. Babe Ruth crushed baseballs, and everyone wanted to see these new-fangled motion pictures--that is, movies. Technology advancements in the area of radios and transmitters allowed people to hear the same news, the same songs, and the same sordid stories about gangsters. Moreover, clothing sytles changed dramatically and so did the English language. Dancing, drinking, and promiscuity were on the rise, fueled by the new music of the time--jazz. In addition, literature flourished, and authors such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway chronicled the decade.

During this era, the Volstead Act prohibited the consumption of alcohol, but many people sought out places to drink illegally in establishments called speakeasies. Another notable legislation passed during this decade was the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.

But the party of the Roaring Twenties came to an abrupt halt in 1929 when the stock market crashed, leading to the Great Depression. The joyous sounds of jazz were soon replaced with such songs as "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime."

A woman dressed in the flapper style of the 1920s

The 1920s did bring profound changes for women. One important change took place with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. The amendment guaranteed women in all states the right to vote. Women also ran for election to political offices. Throughout the 1920s, the number of women holding jobs outside the home continued to grow. Most women had to take jobs considered “women’s” work, such as teaching and working in offices as clerks and typists. At the same time, increasing numbers of college-educated women worked after marriage. But the vast majority of married women remained within the home, working as homemakers and mothers.

The flapper symbolized the new “liberated” woman of the 1920s. Pictures of flappers, carefree young women with short, “bobbed” hair, heavy makeup, and short skirt, appeared in magazines. Many people saw the bold, boyish look and shocking behavior of flappers as a sign of changing morals. Though hardly typical of American women, the flapper image reinforced the idea that women now had more freedom. Pre-war values had shifted, and many people were beginning to challenge traditional ways.

Jack Robin (Al Jolson) sings "Blue Skies" to his mother (Eugenie Besserer) in 1927's The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length film with dialogue sequences.

Changes in attitudes spread quickly because of the growth of mass media, forms of communication, such as newspapers and radio, that reach millions of people. Laborsaving devices and fewer working hours gave Americans more leisure time. In those nonworking hours, they enjoyed tabloid-style newspapers, large-circulation magazines, phonograph records, the radio, and the movies.

In the 1920s, the motion picture industry in Hollywood, California, became one of the country’s leading businesses. For millions of Americans, the movies offered entertainment and escape. The first movies were black and white and silent, with the actors’ dialog printed on the screen and a pianist playing music to accompany the action. In 1927, Hollywood introduced movies with sound. The first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer, created a sensation.

The radio brought entertainment into people’s homes in the 1920s. In 1920 the first commercial radio broadcast, which carried the presidential election returns, was transmitted by station KDKA in Pittsburgh. In the next three years nearly 600 stations joined the airwaves. The networks broadcast popular programs across the nation. The evening lineup of programs included something for everyone, such as news, concerts, sporting events, and comedies. Radio offered listeners a wide range of music, including opera, classical, country and western, blues, and jazz. Amos ‘n’ Andy and the Grand Ole Opry were among the hit shows of the 1920s. Families sat down to listen to the radio together. Businesses soon realized that the radio offered an enormous audience for messages about their products, so they began to help finance radio programs. Radio stations sold spot advertisements, or commercials, to companies.

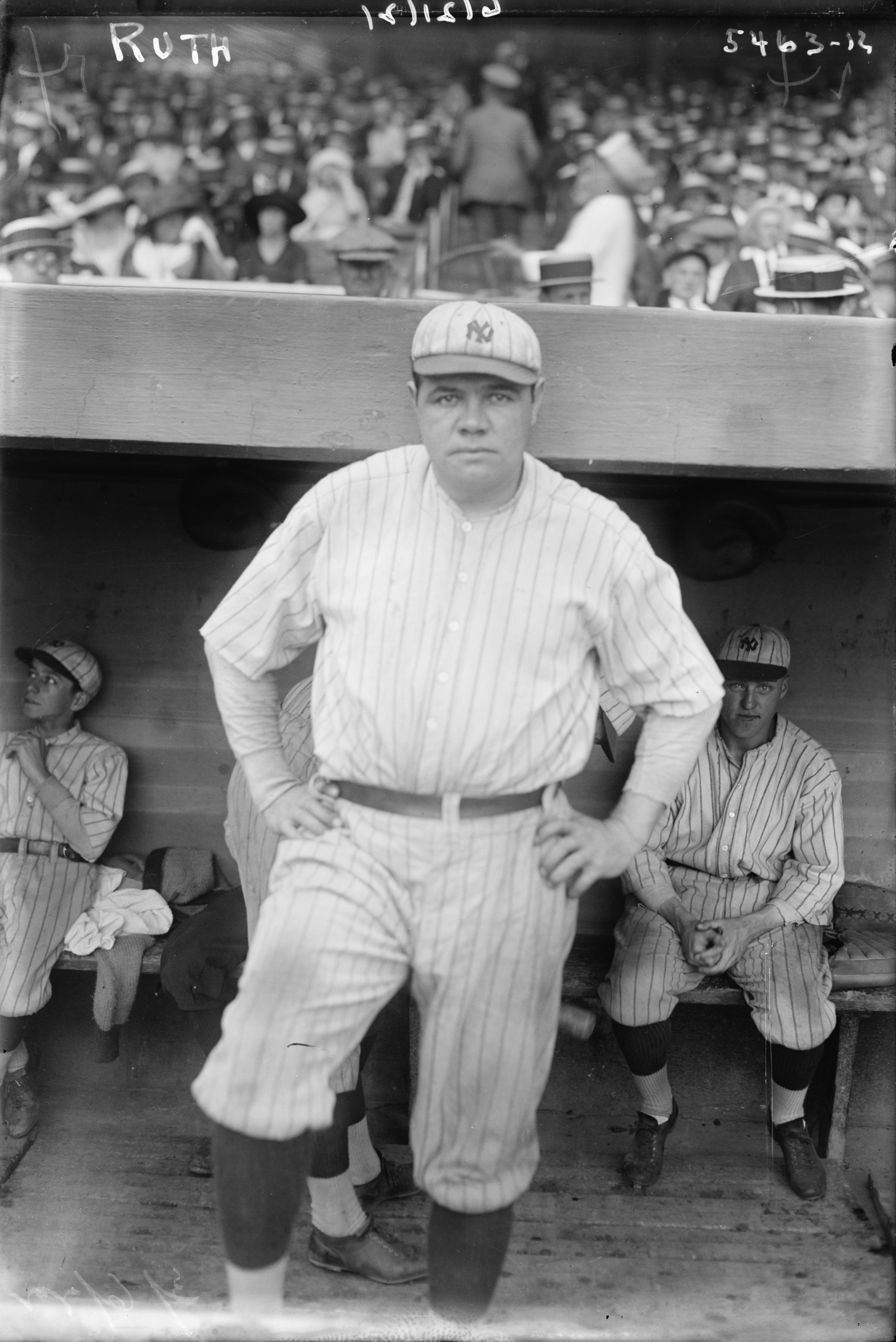

Babe Ruth in 1921

Among the favorite radio broadcasts of the 1920s were athletic events. Baseball, football, and boxing soared in popularity. Americans flocked to sporting events, and more people participated in sports activities as well. Sports stars became larger-than-life heroes. Baseball fans idolized Babe Ruth, the great outfielder, who hit 60 home runs in 1927, a record that would stand for 34 years. Football star Red Grange, who once scored four touchdowns in 12 minutes, became a national hero. Golfer Bobby Jones and Gertrude Ederle, the first woman to swim the English Channel, became household names.

In the 1920s, Americans took up new activities with enthusiasm, turning them into fads. The Chinese board game mah-jongg and crossword puzzles were all the rage. Contests such as flagpole sitting and dance marathons, often lasting three or four days, made headlines. Americans also loved the Miss America Pageant, which was first held in 1921.

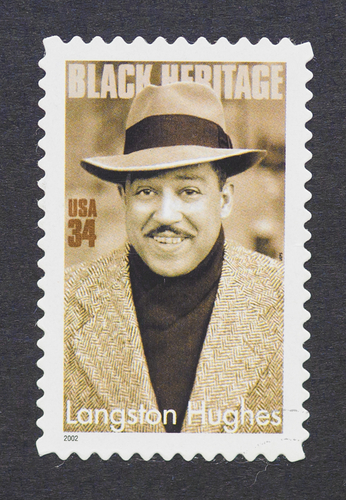

A postage stamp showing an image of poet Langston Hughes

During the 1920s people danced to the beat of a new kind of music called jazz. Jazz captured the spirit of the era so well that the 1920s is often referred to as the Jazz Age. Jazz had its roots in the South in African American work songs and in African music. A blend of ragtime and blues, it uses dynamic rhythms and improvisation, new rhythms and melodies created during a performance. Among the best-known African American jazz musicians were trumpeter Louis Armstrong, pianist and composer Duke Ellington, and singer Bessie Smith. White musicians such as Paul Whiteman and Bix Biederbecke also played jazz and helped bring it to a wider audience. Interest in jazz spread through radio and phonograph records. Jazz helped create a unique African American recording industry. Equally important, jazz gave America one of its most distinctive art forms.

The rhythm and themes of jazz inspired the poetry of Langston Hughes, an African American writer. In the 1920s, Hughes joined the growing number of African American writers and artists who gathered in Harlem, an African American section of New York City. Harlem witnessed a burst of creativity in the 1920s, a flowering of African American culture called the Harlem Renaissance. This movement instilled an interest in African culture and pride in being African American. During the Harlem Renaissance, many writers wrote about the African American experience in novels, poems, and short stories. Along with Hughes were writers like James Weldon Johnson, Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neale Hurston.

While the Harlem Renaissance blossomed, other writers were questioning American ideals. Disappointed with American values and in search of inspiration, they settled in Paris. These writers were called expatriates, people who choose to live in another country. Writer Gertrude Stein called these rootless Americans “the lost generation.” Novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, joined the expatriates in Europe. In Tender Is the Night, Fitzgerald wrote of people who had been damaged emotionally by World War I. They were dedicated, he said, “to the fear of poverty and the worship of success.”

Another famous American expatriate was novelist Ernest Hemingway, whose books The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms reflected the mood of Americans in postwar Europe. While some artists fled the United States, others stayed home and wrote about life in America. Novelist Sinclair Lewis presented a critical view of American culture in such books as Main Street and Babbitt. Another influential American writer was Sherwood Anderson. In his most famous book, Winesburg, Ohio, Anderson explored small-town life in the Midwest.

Prohibition agents stand with a still and mason jars used to distill hard liquor in the Washington, D.C., area on November 11, 1922.

During the 1920s the number of people living in cities swelled, and a modern industrial society came of age. Outside of the cities, many Americans identified this new, urban society with crime, corruption, and immoral behavior. They believed that the America they knew and valued, a nation based on family, church, and tradition, was under attack. Disagreement grew between those who defended traditional beliefs and those who welcomed the new.

The clash of cultures during the 1920s affected many aspects of American life, particularly the use of alcoholic beverages. The temperance movement, the campaign against alcohol use, had begun in the 1800s. The movement was rooted both in religious objections to drinking alcohol and in the belief that society would benefit if alcohol were unavailable. The movement finally achieved its goal in 1919 with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment established Prohibition. a total ban on the manufacture, sale, and transportation of liquor throughout the United States. Congress passed the Volstead Act to provide the means of enforcing the ban. In rural areas in the South and the Midwest, where the temperance movement was strong, Prohibition generally succeeded. In the cities, however, Prohibition had little support. The nation divided into two camps: the “drys”, those who supported Prohibition, and the “wets”, those who opposed it.

A continuing demand for alcohol led to widespread lawbreaking. Some people began making wine or “bathtub gin” in their homes. Illegal bars and clubs, known as speakeasies, sprang up in cities. Hidden from view, these clubs could be entered only by saying a secret password. With only about 1,500 agents, the federal government could do little to enforce the Prohibition laws. By the early 1920s, many states in the East stopped trying to enforce the laws. Prohibition contributed to the rise of organized crime. Recognizing that millions of dollars could be made from bootlegging, making and selling illegal alcohol, members of organized crime moved in quickly and took control. They used their profits to gain influence in businesses, labor unions, and governments.

Crime boss Al “Scarface” Capone controlled organized crime and local politics in Chicago. Eventually, Capone was arrested and sent to prison. Over time many Americans realized that the “noble experiment,” as Prohibition was called, had failed. Prohibition was repealed in 1933 with the Twenty-first Amendment.

Clarence Darrow (standing at right) interrogates William Jennings Bryan; proceedings of the Scopes Trial were held outside due to the extreme heat of July 20, 1925.

Another cultural clash in the 1920s involved the role of religion in society. This conflict gained national attention in 1925 in one of the most famous trials of the era. In 1925, the state of Tennessee passed a law making it illegal to teach evolution, the scientific theory that humans evolved over vast periods of time. The law was supported by Christian fundamentalists, who accepted the biblical story of creation. The fundamentalists saw evolution as a challenge to their values and their religious beliefs.

A young high school teacher named John Scopes deliberately broke the law against teaching evolution so that a trial could test its legality. Scopes acted with the support of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). During the sweltering summer of 1925, the nation followed day-to-day developments in the Scopes trial with great interest. More than a hundred journalists from around the country descended on Dayton, Tennessee, to report on the trial. Two famous lawyers took opposing sides in the trial. William Jennings Bryan, Democratic candidate for president in 1896, 1900, and 1908 and a strong opponent of evolution, led the prosecution. Clarence Darrow, who had defended many radicals and labor union members, spoke for Scopes.

Although Scopes was convicted of breaking the law and fined $100, the fundamentalists lost the larger battle. Darrow’s defense made it appear that Bryan wanted to impose his religious beliefs on the entire nation. The Tennessee Supreme Court overturned Scopes’ conviction, and other states decided not to prosecute similar cases. The Scopes case may have dealt a blow to fundamentalism, but the movement continued to thrive. Rural people, especially in the South and Midwest, remained faithful to their religious beliefs. When large numbers of farmers migrated to cities during the 1920s, they brought fundamentalism with them.