World War I was hard on Russia. They lost hundreds of thousands of men fighting Germany in the war. Afterwards, the Russian czar was overthrown by the Bolsheviks, a labor party led by Vladimir Lenin. This was the first communist regime based on the ideas of Karl Marx. This revolution had an effect on labor in America, as well as laborers who were still calling for better wages. In 1919, a group of American radicals formed the Communist Labor Party, which terrified the American government.

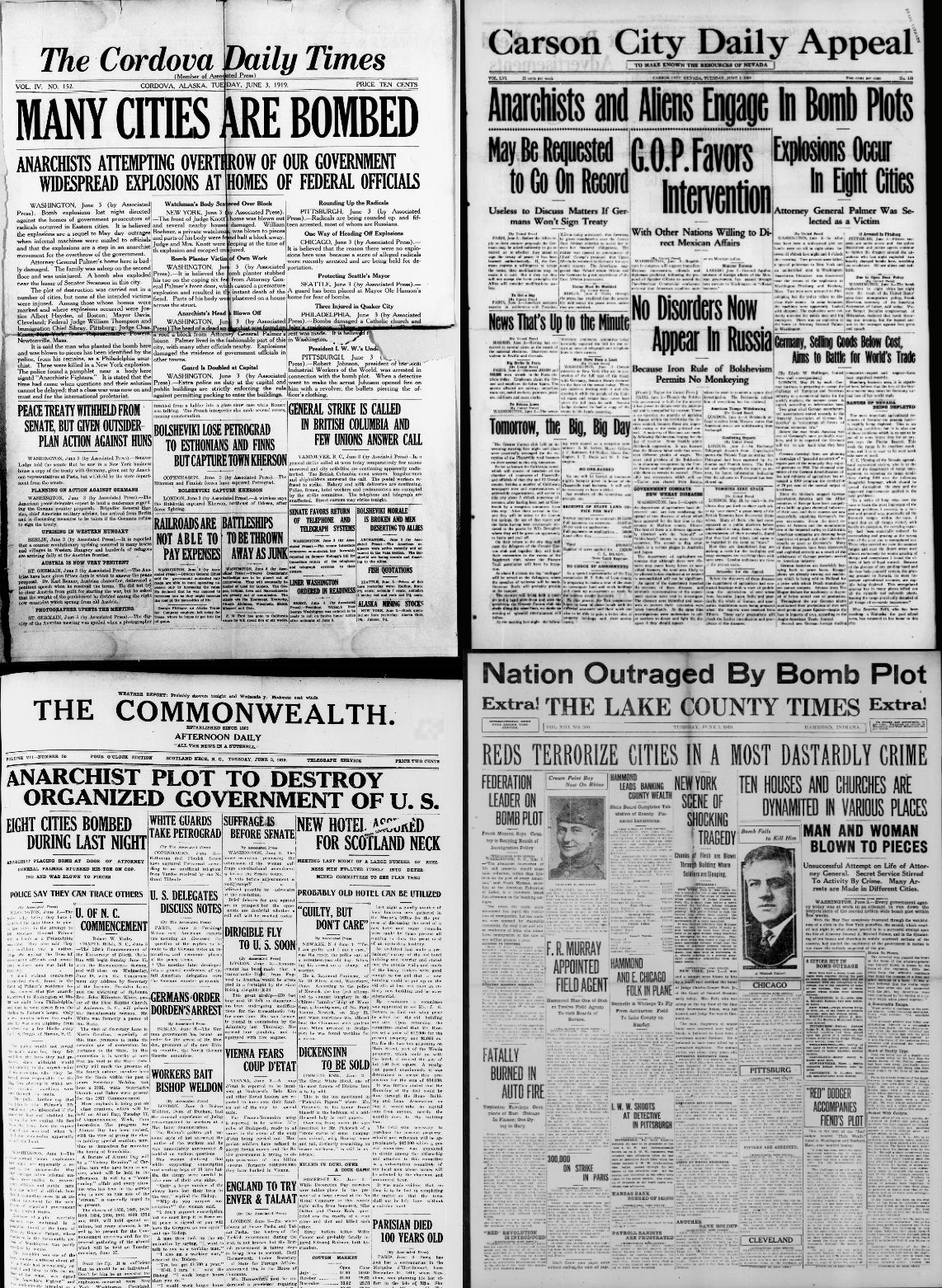

Newspaper coverage of the 1919 anarchist bombings

Most of the 1920s was anything but unified. During World War I, the United States government had taken away some of the liberties of American citizens. Many people who opposed the nation’s role in the war were arrested. After the war, an atmosphere of distrust remained. Tired of war and world responsibilities, Americans were eager to return to normal life. They grew more and more suspicious of foreigners, foreign ideas, and those who held views different from their own. In 1919, Wilson and the world leaders attending the peace conference signed the Treaty of Versailles. Despite Wilson’s efforts, however, the Senate refused to ratify the treaty.

At about the same time, the Russian Revolution deeply disturbed some Americans. The Bolsheviks took control of Russia in November 1917 and began establishing a Communist state. They encouraged workers around the world to overthrow capitalism anywhere it existed. Many Americans feared that “bolshevism” threatened American government and institutions. Fanning those fears were the actions of anarchists, people who believe there should be no government. A series of anarchist bombings in 1919 frightened Americans. Several public officials, including mayors, judges, and the Attorney General of the United States, received packages containing bombs. One bomb blew off the hands of the maid of a United States senator. Many of the anarchists were foreign-born, which contributed to the fear of foreigners that was sweeping the country.

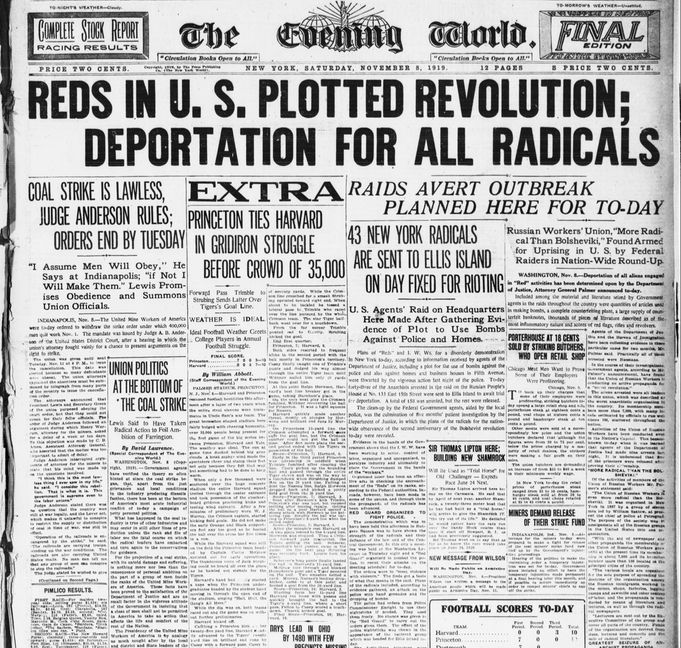

A headline in the November 8, 1919, edition of The Evening World newspaper reflects the anticommunist views of the Red Scare.

This wave of fear led to the Red Scare, a period when the government went after “Reds”, as Communists were known, and others with radical views. In late 1919 and early 1920, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and his deputy, J. Edgar Hoover, ordered the arrest of people suspected of being Communists and anarchists. Palmer and Hoover also staged raids on the headquarters of various “suspicious” groups. In the raids, the government arrested a few thousand people, ransacked homes and offices, and seized records. They did not find the large stockpiles of weapons and dynamite they claimed they were seeking.

Palmer said the raids were justified. “The blaze of revolution was sweeping over every American institution of law and order,” he declared, “burning up the foundations of society.” The government deported—expelled from the United States—a few hundred of the aliens it had arrested but quickly released many others for lack of evidence. In time, people realized that the danger of revolution was greatly exaggerated. The Red Scare passed, but the fear underlying it remained.

The Massachusetts State Guard detains suspects during the Boston police strike of September-October 1919.

During the war years, labor and management had put aside their differences. A sense of patriotism, high wages, and wartime laws kept conflict to a minimum. When the war ended, conflict flared anew. American workers demanded increases in wages to keep up with rapidly rising prices. They launched more than 2,500 strikes in 1919. The wave of strikes fueled American fears of Bolsheviks and radicals, whom many considered to be the cause of the labor unrest.

A long and bitter strike, the largest in American history to that point, occurred in the steel industry. Demanding higher wages and an eight-hour workday, about 350,000 steelworkers went on strike in September 1919. Using propaganda techniques learned during the war, the steel companies started a campaign against the strikers. In newspaper ads, they accused the strikers of being “Red agitators.” Charges of communism cost the strikers much needed public support and helped force them to end the strike—but not before violence had occurred on both sides. Eighteen strikers had died in a riot in Gary, Indiana. In September 1919, police officers in Boston went on strike, demanding the right to form a union. This strike by public employees angered many Americans, and they applauded the strong stand Massachusetts governor Calvin Coolidge took against the strikers. When the strike collapsed, officials fired the entire Boston police force. Most Americans approved of the decision.

Workers found themselves deeper in debt because of rising prices and unchanged wages. Still, labor unions failed to win wide support among working families. Many Americans connected unions with radicalism and Bolshevism. A growing feeling against unions, together with strong pressure from employers and the government not to join unions, led to a sharp drop in union membership in the 1920s.

During this period of union decline, a dynamic African American, A. Philip Randolph, started the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Made up mostly of African Americans, this union of railroad workers struggled during its early years but began to grow in the 1930s, when government policy encouraged unions. In the 1950s and the 1960s, Randolph would emerge as a leader of the civil rights movement.